This episode we travel to a future where the 2020 census goes haywire. What happens if we don’t get an accurate count of Americans? Who cares? Apparently the constitution does!

The 2020 census is currently in the crosshairs — census watchers say that it’s not getting enough funding, and community organizations and local governments are already worrying about what an inaccurate census might mean for their people.

To walk us through the current perils facing the census I talked to Hansi Lo Wang, a national correspondent for NPR who has been covering the census; Phil Sparks, the co-director of The Census Project, an organization that brings together groups who use census data; Susan Lerner, the director of Common Cause New York, a government watchdog group; Cayden Mak, the executive director of 18 Million Rising, an online organizing group that works with Asian American communities; and Dawn Joelle Fraser, a storyteller and communications coach who worked for the census in 2010.

Further reading:

- Could A Census Without A Leader Spell Trouble In 2020?

- US Census Director Resigns Amid Turmoil Over Funding of 2020 Count

- Departure of U.S. Census director threatens 2020 count

- The 2020 Census is at risk. Here are the major consequences

- With 2020 Census Looming, Worries About Fairness and Accuracy

- Trump’s threat to the 2020 Census

- NAACP lawsuit alleges Trump administration will undercount minorities in 2020 Census

- Census 2020: How it’s supposed to work (and how it might go terribly wrong)

- Census watchers warn of crisis if 2020 funding is not increased

- Likely Changes in US House Seat Distribution for 2020

- What Census Calls Us: A Historical Timeline

- As 2020 Census Approaches, Worries Rise Of A Political Crisis After The Count

- The American Census: a social history by Margo J. Anderson

- The Story Collider podcast: Dawn Fraser, The Mission

Note: This is the second to last episode of this season of Flash Forward! The last episode drops January 9th, and then the show will be in hiatus for a few months while I prep for season 4, which is going to be great I can already assure you! If you want to follow along with the prep for season 4, and just generally keep up with what’s going on with the show and when it’s coming back stay in touch via Twitter, Facebook , Reddit, or, best of all, Patreon, where I’ll post behind the scenes stuff as I get ready for the next Flash Forward adventures.

Also, I’m going on tour with PopUp Magazine in February! Get your tickets at popupmagazine.com.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. Special thanks this week to Liz Neeley who voiced our discouraged bureaucrat. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

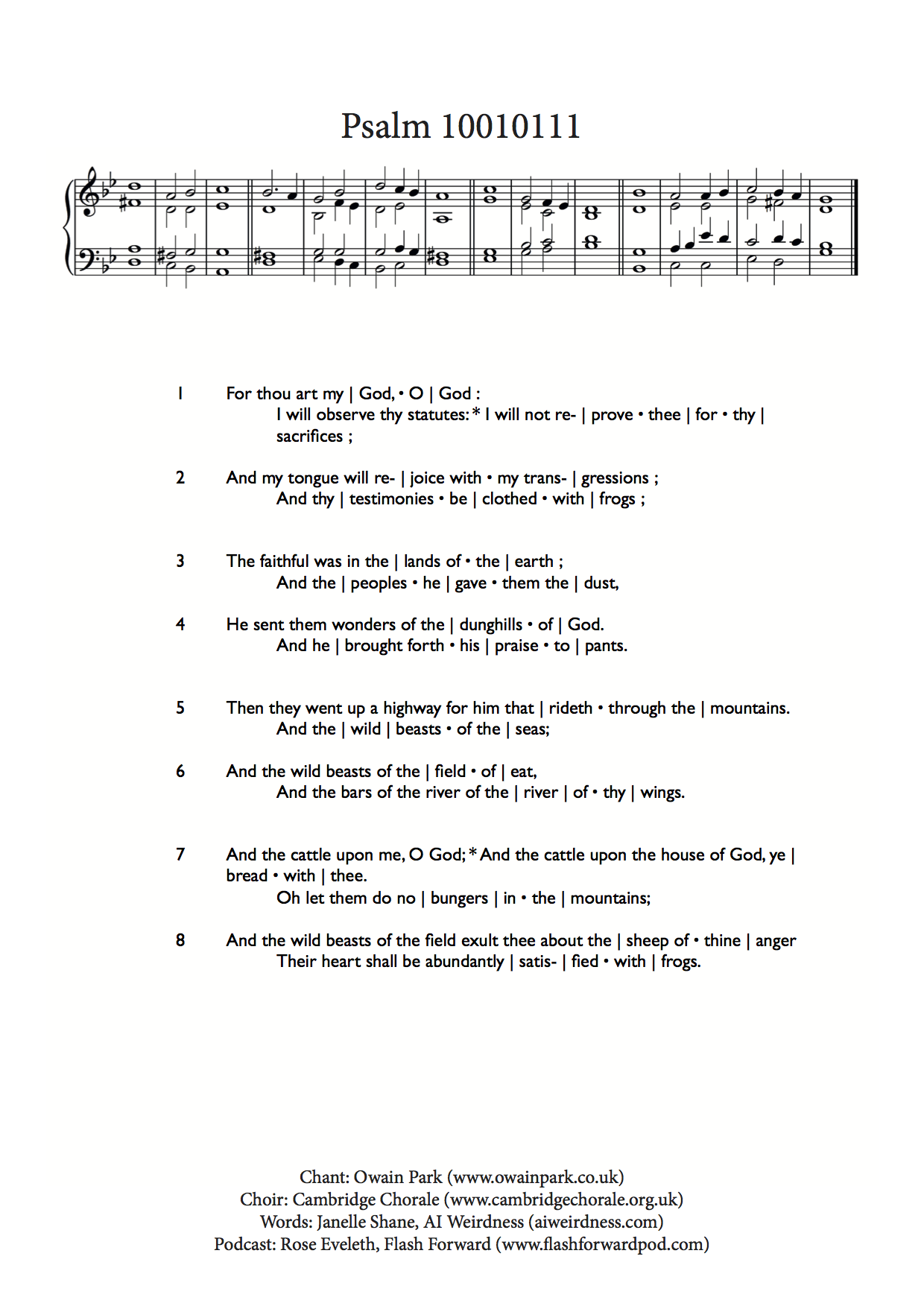

As a bonus, at the end of this episode, you’ll hear a human chorus record a psalm that was written by Janelle Shane’s machine learning algorithm. (Remember her from the super religion episode?) Here’s the arrangement of that psalm by Hamish Symington and Owain Park:

And here’s the psalm recorded by Tim Rosko, Nick Tiberi and Emily Swora:

This episode is supported in part by:

- BetterHelp, convenient, affordable, private online counseling. Enter the invite code FLASH to get your first 7 days free

▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹

TRANSCRIPT

Rose: Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible… or not so possible future scenario. We always start with a little field trip to the future, to check out what’s going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to experts about how that world we just heard might really go down. Got it? Great!

Before we go to the future, I have two things to tell you.

First: This is the second to last episode of this season of Flash Forward! The last episode will drop January 9th, and then the show will be on hiatus for a couple months while I prep for season four. If you want to keep up with what is going on and when the show is coming back, follow us on Instagram or Twitter or Facebook, or, better yet, become a Patron and you’ll get behind the scenes information about season four and all the weird fun stuff I have planned.

Second thing to tell you before we go to the future: I have a super fun surprise for you at the end of this episode. Remember two episodes ago when we talked about a futuristic religion generated by a super computer? Well, as part of that algorithmic experiment, our machine learning wrangler Janelle Shane also had her system generate a psalm based on a big corpus of psalms. Then, two guys in the UK named Hamish Symington and Owain Park arranged that computer generated psalm for an actual choir. And then, three amazing people named Tim Rosko, Nick Tiberi and Emily Swora got their choir together, and they actually sang the computer generated psalm. It is delightful and so weird, and you can hear the song at the very end of this episode, so stick around for that. It’s so worth it.

Okay, now on to the future! This episode we’re starting in the year 2020.

Census Commercial: Keeping check of where we are, and where we’re going is still our common purpose in the census.

Our separate identities will be lost in the process, which is concerned only with what we say, not who said it.

Government Official: Welcome back to day number two of the CSAC fall meeting. Following a very lively, and rich, presentation and discussion yesterday, we’re on to day number two. Some of you may recall, last meeting I started a tradition called, “who said that?”. Of course, this was not really a quiz, you didn’t have to answer…

Government Official: We thank you very much for your testimony and for your service to the United States. Article I, Section II of the constitution of course requires the congress to conduct an actual enumeration of the population every ten years. Ever since the very first one was done by my favorite founding father, Thomas Jefferson, we’ve met that goal. Although it hasn’t always been under budget, and that’s a primary source of concern for this subcommittee, and a focus of a lot of our conversation today is to focus on what we can do to ensure that the census is done under budget.

Effren Herrera: I am Effren Herrera of the Seattle Seahawks, and this is my family. Hola, soy Effren Herrera de los Seattle Seahawks, y esta mi familia.

Elvin Hayes: Hi, I’m Elvin Hayes of the Washington Bullets.

Lou Brock: I’m Lou Brock of the St. Louis Cardinals.

Sugar Ray Leonard: I’m Sugar Ray Leonard

Roger Staubach: I’m Roger Staubach of the Dallas Cowboys.

Franco Harris: The census shows where your community and mine need help

Martina Navratilova: We need an accurate count of our communities. Thats’ how we get help where the help is needed. For jobs, schools, hospitals. And look, don’t worry. Your name and answers will be kept absolutely secret. That’s the law. So make sure you’re counted in America’s future. Answer the census on April 1st. I’m going to.

Government Official: As you all know, the 2020 Census is in full swing. And, as you also know, this year’s census has been systematically and continuously underfunded, which has resulted in a series of cuts to the planned program and ramp up of the census. No doubt, many of you have heard the news stories of fraudulent online census forms. Last week, this very body voted to shut down the online census system in favor of mailing additional paper surveys.

I regret to report that these issues are indeed having a clear impact on the quality of the census. Traditionally, at this point in the process we would expect to have about 75 percent of all households reporting. Instead, we are at 45 percent. The floor is now open to committee members with ideas for how to boost the response rate, but please remember, your proposal must come with funding ideas as well, as we are completely out of money.

[gavel]

Rose: Okay, so this future is one in which the 2020 United States census is considered a failure. Now this is something that, some people in the US are actually really worried about. Because the 2020 Census is already not going that well.

Hansi Lo Wang: Ha. Where do I start. There’s a lot of uncertainty at the Census Bureau. The Census Bureau has asked for more money than Congress has been appropriating, so it says it’s being underfunded. There is also uncertain leadership at the Census Bureau. The last director just left, there are a number of other leadership positions below the director of the Census Bureau that also are in flux. And this is coming just about two years before census day 2020.

My name is Hansi Lo Wang I’m a national correspondent for NPR, and I covered the census.

Rose: All of this confusion at the census is already having a real impact. Due to lack of funds, the census bureau has had to cancel two field tests that were meant to try out the latest surveys and methods for collecting census data in 2020. And that’s especially troubling for this particular census…

Hansi: The 2020 census is going to be a super ambitious census. It’s going to be the first one mainly conducted online. Because it’s the first internet census, there’s a lot at stake because… “how is this going to work? Will the website crash when they launch this website? Will people actually fill it out? How will people fill it out? Can anyone hack this system? Will there be any security breaches?

Rose: All those questions cost money to answer, and right now the census bureau claims that it doesn’t have enough money, and Congress is still trying to decide whether to hand that money over. And people who work with and rely on the census are starting to worry that soon, it might actually be too late.

Phil Sparks: We put off all the major decisions in terms of funding until right now. Winston Churchill used to say, that in terms of Americans, they could always be counted on to do the right thing after they looked at every other possible option. Well we’re now at that point that Winston Churchill talked about.

Rose: This is Phil Sparks, the co-director of The Census Project, which is a non-partisan group made up of organizations that rely on census data. Things like labor unions and businesses and civil rights organizations. And Phil isn’t alone in worrying about whether or not the census is going to get the money and support it needs.

Susan Lerner: You have this gigantic venture which takes enormous planning, huge amounts of detail, and has to be adequately funded. Well, in its infinite wisdom, the wonderful people in our Congress decided several years ago that they would insist that the money spent for the 2020 census could not be any more than the money spent for the 2010 census.

Rose: This is Susan Lerner, the executive director of Common Cause NY, a government watchdog group.

Susan: Now I don’t know about you, but there’s virtually nothing in my life that costs as little as it cost in 2010, which wasn’t so little to begin with. Prices have gone up. So if you keep the amount of money steady you have a problem.

Phil: As the months drag on, and Congress comes to no conclusion in terms of the federal government, and therefore no conclusion in terms of the Census Bureau’s budget, it’s not only worse but at some point it will become if it will seriously affect the census and its accuracy. Because we’re going to take a census. The question is is it going to be a good one and a fair one, or is it going to be a bad one.

Rose: It’s unclear if the money is going to come, in part because politicians and pundits have zeroed in on the census as a place to cut money from the budget. Here’s a clip from a Fox News roundtable discussion from last year:

[[FORBES ON FOX CLIP]]

Mike Ozanian: As for what can be cut, I’d love to see the $8 Billion slated for the 2020 census get slashed. I think the census is unamerican. The last census, the woman came to my house, she was asking me where my grandparents came from, where I came from, what race I was. Why does it matter?

David Asman: We don’t need it! We don’t need it! We could save money, and our own privacy by getting rid of it!

Rose: So the 2020 census might very well not get the money it’s asking for. And that might impact how good the census actually is. And, that might not seem like such a big deal. I mean… who cares if we don’t have an exact count of the exact number of people in the US and where they live? Who cares if we only get a census response of 90 percent of the US instead of 99 percent?

Phil: Well if it was 90 percent it would have been a catastrophe, and it would have been a disastrous census. I would say that if the census was was 2 percent inaccurate, in other words we only counted 98 percent of the public, then it probably is an inaccurate census and there would be a political hell to pay. And we would surely have a constitutional crisis.

Rose: A constitutional crisis. But why? In order to understand why a 3 or 4 percent drop in census accuracy would be such a big deal, we need to actually understand first what the census… actually is. So let’s back up to the founding of the United States.

It’s 1787, and the founding fathers are meeting in Philadelphia to try and figure out how to run this new country of theirs. Which is obviously no small task, you have these states who want their rights, but you also need to figure out how to govern the collective as a whole. The conglomeration that is the United States of America, how do you unite them? You have tiny states and big states, you have populous states and you have empty states. And you have a ton of land to the West which you know you’re going to go steal sooner or later… So the founding fathers were presented with this immense challenge: figuring out a system that could accurately and fairly represent all of those things.

So, at this meeting in Philadelphia, you have representatives from already existing states, and they’re all trying to make sure that they don’t get screwed over in whatever the system winds up being. So if you’re a tiny state with not that many people, you are all for a government that gives every state the same number of representatives. But if you’re a huge state with lots of people, you’re like “wait a minute, I should get more of a say since I have way more people.” So the founding fathers decided to do both — and the US has a Senate in which every state gets two senators. And a House of Representatives where each state gets a bunch of representatives, depending on how many people they have. You probably already know all of this, but it’s good to all be on the same page, because this is where the census comes in.

Once they decided on having a House of Representatives, the founding fathers realized that they still had to figure out how that House of Representatives was going to work. How many seats should there be in the house? And how do you figure out how many people are in each state, so that you can figure out how many representatives they should have? Well… obviously you have to count everybody. And thus, the census was born and written into the constitution.

Here’s how Section 2, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution explains the census.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

This is actually where the whole concept of slaves being only 3/5ths of a person comes from. And we’re going to come back to that when we talk about the ways in which the census does or doesn’t count certain people.

But by tying the census to both representatives and to taxes, the founding fathers were able to cut off any kind of cheating. States that tried to overestimate their populations to get more seats, would wind up then being taxed more because they had more people. And states that tried to weasel out of taxes by undercounting their people, would lose representatives in congress.

But there was one other thing that they had to stipulate about the census. You can’t just count once and call it a day, The founding fathers knew that the US was going to grow. It already had grown a ton. In 1700, there were about 250,000 colonial settlers living in the US. By 1780, that number had jumped to 2.8 million. So the founding fathers wrote one more thing about the census into the constitution:

The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first meeting of the congress of the United States and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.

The fact that the census is written into constitution and is a key part of the mechanism by which our entire government functions makes the argument that the census is “unamerican” kind of hilarious.

Phil Sparks: The three advocates among our founding fathers for the census were Benjamin Franklin, James Monroe, and Thomas Jefferson. And they basically wrote into our nation’s constitution a mandate that the census must be taken every ten years.

And for as long as we’ve had the census, it’s been more difficult and expensive than we expected.

The first census, which was overseen by our first president, George Washington in 1790, was supposed to take nine months. It took eighteen months, and the field marshals in charge and their 650 assistants really struggled to go door to door to collect all of the information that they needed. The final count was 3.9 million people, and Washington suspected that it was too low. But it was done.

What Washington maybe didn’t realize was that the counting was only the beginning. They then had to figure out what to actually do with those numbers. Now that you know how many people live in each state, how do you divvy up the seats in the house based on those numbers? Some people wanted states to get one representative for every 30,000 residents. Others proposed one for every 33,000 residents. The way that the seats were going to be distributed, was a huge controversy that lasted for a year. In fact, the first ever presidential veto was used by George Washington to veto a bill that outlined a method of doling out representatives that the South hated.

But eventually, in April of 1792, the final decision was made. The House would have 105 seats in it, and states would be given one representative for every 33,000 individuals.

Now, today, that’s not exactly how it works. As the United States grew, so did the House of Representatives. And today, if we gave each state one representative for every 33,000 residents, the house of representatives would have 9893 seats in it. Which… is unwieldy. So eventually the rules were changed. Today House of Representatives has a set number of seats. But the way that those seats are divvied up is still based entirely on the census.

Susan: We set our political boundaries for electing members of Congress, state legislatures, city councils, county legislatures. They’re all set based on the population numbers of the census.

Rose: In fact, every ten years, when the census rolls around, states start to worry that they might lose seats in the House of Representatives because of census numbers.

LOCAL NEWS

Newscaster: Some political science analysts believe that nebraska could be in danger of losing a congressional seat after the 2020 census, because it’s not growing as fast as other states.

Rose: But that’s not the only way that census data impacts Americans. It’s also used as a way to figure out how to divide up funding.

Hansi: The federal government relies on these numbers to distribute more than 600 billion dollars a year in federal grants and federal funding. And this goes to local state governments.

Phil: Things like Medicare, Medicaid, health insurance, Head Start, school lunch programs, highways and roads; for instance California gets about 80 billion dollars a year for these activities. All of it relies on census counts.

Hansi: So. if you don’t have the numbers, how do you figure out, essentially how do you cut up this pie and make sure everyone’s getting a fair share?

Rose: Often, the federal programs that use census data to distribute money, are programs designed to help the most at-risk populations.

Phil: Take Head Start for instance; the money is directed towards a particular population, the Pre-K population in the United States. And it’s particularly directed towards people in low income, working poor, working areas where they need particular help in terms of Pre-K assistance. The census identifies in each community, how many people in each community, how many families there are, how many children there are of that age. And basically, uses as a formula so that that money then from the federal government, once it’s appropriated, is guided based on a formula, to particular communities to use for Head Start activities when they have a Head Start program. So that’s how it’s done.

Rose: And it’s not just the government that uses this data, businesses actually rely on census data to make decisions too. When a business is trying to figure out where to put a store, or where to hire more people, they turn to census data.

Susan: So, you’re a retail corporation, right? Let’s say you’re, I don’t know, Macy’s may not be a good example, but you’re you’re a retail corporation. You’ve decided that you do want to expand into some new markets. You have choices among three or four different upstate areas. You’re looking at Utica, you’re looking at Rochester, you’re looking at Syracuse, you’re looking at Binghamton. And you want to see what the census trending figures are, where do you have growing population in a certain socio economic strata? Well, if the census figures are off by a significant amount, then you could be putting your new store in Binghamton, but that part of the census is wrong and your customers are really in Rochester. So you’ve just spent a lot of money and effort in Binghamton for a store that may fail. And that’s a complete and that’s a completely made up example, but that’s one of the ways in which this data is used.

Rose: This is all to say that the census is way more important than you might have realized. It’s way more important than I realized before researching this episode. I just thought it was kind of a big, boring government thing that they just sort of had to do.

So if the 2020 census doesn’t get funded fully, and it winds up really undercounting the US population… what happens? Phil said earlier there would be a constitutional crisis, but when we come back we’re going to drill down into exactly what might happen next, and who would feel the impacts most.

Okay, so this episode is all about what might happen if the 2020 census fails. So the 2020 census is going to happen. It’s not like it’s going to be cancelled. But without funding, it might struggle in a couple of key areas. The first one we already talked about — not testing the survey before it goes live. But the second one is that it might not have enough money to hire all the people that it needs.

Phil: So, it’s a massive undertaking. It’s usually taken by about 500,000 census takers, going door to door to more than 130 million residences across the United States.

Rose: In 2010, the census bureau hired over 600,000 people to go door to door. People like Dawn Fraser

Dawn Fraser: My name Dawn Fraser, I’m a storyteller, a speaker, and a communications coach. My background was in public policy. I did a master’s in public policy, so I’ve always been interested in communities and people. At the same time, I needed a fricking job, I needed to get paid. 2010 was coming out of that slump of 2008. And I had this master’s degree, and I couldn’t get a job.

So I was in this rut, and then I saw a sign for the census. I also had a little bit of a secret mission to try and find the single people in my neighborhood. I figured that that would be a lot easier than trying to get on Match.com. The census had their mission and I had mine.

Rose: When you go out on a census mission, you’re always partnered up with someone.

Dawn: One of my favorite people was a woman that lived down the street from me, in my neighborhood. She was 65 years old plus, and it was a lot of fun to be able to connect with somebody who had lived in the neighborhood her entire life, considering I had just I had just moved in. And so it was me, and this woman’s name as Eloise. So Eloise and I would just go knocking on people’s doors, having a good time chatting about life, chatting about the changes of Brooklyn, changing the neighborhood, and what was going on.

Rose: So Dawn and Eloise went down their list of addresses for people who hadn’t yet filled out the census.

Dawn: It was interestingly easy for a lot of people. I think that once you actually track down the person, they are typically interested in talking because they’re like. “Who’s knocking on my door?” You know, in 2010, people knocking on your door, that’s kind of a weird thing. It’s like, “Why? Why are you coming to my door?” And so I think that once they realize that it’s somebody from the census, and a kind of curious about who they are, then they tend to loosen up a bit.

Rose: Phil Sparks, the co-director of the Census Project, has also been a census taker.

Phil: At about six weeks, you began going door to door, and what happens is you say, “boy this is going to be a great job.” Because you knock on some doors, and you find out that about 60 or 70 percent of the people that have been keyed in by the Census Bureau that you need to get the forms, you get those forms. “Boy this is not going to be too hard.”

Rose: But other times, that’s not how it went.

Dawn: In other cases, they were not coming outside. And I realized that there was some situations where it may have been a family that had some people who are maybe not here legally. Or maybe just did not want to talk to a stranger. So, it was interesting to see how people would respond, depending on where they were living. And what their lifestyle was. Because I think that some of the people who are on the fringes of society probably still aren’t counted, to be honest with you.

Rose: And this brings us to something really important about the census, and something that will be magnified if the 2020 census goes awry, and if big groups of people don’t get sent out into the field to try and count people. And that’s what statisticians call a “differential undercount.” Basically what this means is that some groups of people are far more likely to be undercounted than other groups of people.

Cayden Mak: The census undercounts Asian American communities by as much as a million people. Which is a little bit mind blowing when you think about the fact that there are about 21 million Asian Americans, more or less. So when we’re talking about an undercount of a million people, we’re talking about a pretty large percentage. Almost 5 percent.

Rose: This is Cayden Mak.

Cayden: I’m the executive director at 18 Million Rising dot org. We’re an online organizing group that works with Asian American communities.

You know a lot of Asian American communities, especially recent immigrants, come from countries where the government has used counting and indexing to repress dissent, and in some cases to commit genocide. And so, convincing them that responding to the census is a good idea is a little more complex than saying, “Oh, we’ll give your community access to resources.” It’s also like, “Do we trust this government enough?”

Rose: Technically, specific census data, as in, your name and where you live, is confidential. But general census data — the fact that, say, a large group of Japanese Americans live in a certain neighborhood, for example — is public. And that data has indeed been used against people.

Hansi: There is a history of Census Bureau data being used, for example, to kind of round up Japanese Americans during World War II, and that’s always a historical case that’s brought up of why people have fears of giving up information.

Rose: Undercounting certain groups is not a new problem for the census. Remember that when the census was founded, it literally only counted slaves as 3/5ths of a person. But for a long time, the census didn’t really even know it had this problem. They knew that they were never getting everybody, but they didn’t really consider that they might be undercounting some groups more than others. It wasn’t until around 1941 when they started to realize that the undercount might not be evenly distributed.

Phil: In 1940, when they did the census, they seriously, by several million people, undercounted rural black young males. And the only reason they knew this was because when the selective service draft Act went into place in 1941, 2 million more southern black males from mostly rural areas showed up to register. So they knew they had a problem. To that point, I’m not even sure they thought much about the undercount, much less a differential undercount.

Rose: Today, the census has a very good picture of which groups are hardest to count. And in the past, the Census Bureau has spent a lot of money trying to make sure that those groups are attended to.

Cayden: Some of them are really simple, common sense, things, like sending people a letter before the actual census forms are sent. To say, “Hey this is happening. Here’s what it’s about. Here’s some answers to some common questions.” And then allowing people to request an in language form then and there is a really big deal.

Rose: Or even just hiring folks from the community to go out and collect census data.

Cayden: A generic message to a community of Hmong refugees is maybe not going to land in the same way that a message from other Hmong speakers, other Asian Americans who have refugee backgrounds, might land. And stuff like that, when budgets get cut, and when there’s a lack of leadership, those are the things that I worry about falling by the wayside, even though they’re shown to to increase the count.

Rose: Which could really impact these communities.

Susan: The populations that historically have been undercounted are also the populations which historically are economically and socially disadvantaged. They’re the populations that the government tries to assist. And if you don’t have an accurate sense of people who need help, then you can’t have an effective program to help them. You are not putting in enough resources. You’re not going to where the people who actually need the help can be found. Your efforts are misdirected, and they’re too short of the mark. And that happens way too frequently, and it shouldn’t happen because we just haven’t accurately counted who needs the help. THat’s the most basic thing. Where we have limited political will to help people. We certainly shouldn’t be misapplying what little resources we have because we don’t have an accurate count.

Cayden: The consequences here are not just about the next five or 10 years. When we talk about the allocation of money for education, for instance. And especially bilingual education, and that kind of thing; that has potentially generational consequences. Right? And that what we neglect today, come back and bite us in the ass tomorrow in a very real way. Especially where education and health care is concerned.

Rose: But, let’s go to 2020. Let’s say we’re in 2020, how would we even know that the census is failing? There has never been a failed census before — or at least there has never been a census that was officially considered failed. So how would we know if the census wasn’t going well?

Susan: If you have a mail return rate a return rate of 73 percent or less, they’re considered hard to count area. So if your accuracy is falling below that level, you’re not getting most of the people to answer, I don’t know that anybody would consider it a failed census. I haven’t heard that term, but it would be an accurate census. It might not be a reliable census and that would be a tragedy.

Rose: In 2020, the census is actually going to coincide with a presidential primary. Which… if the last presidential primary is any indication, is going to be a pretty intense period. And Hansi says that if the census isn’t going well, we’re going to hear about it pretty quickly.

Hansi: I think, towards the end of 2020 and in spring of 2021, when these numbers start coming out and people are thinking about redistricting and thinking about, “It’s been 10 years.” A mayor may be thinking, “It’s been ten years. My city certainly has grown. I need to make sure I can ask for more money, and make sure I get enough federal funding that I think my city deserves. And that’s because my population is growing,” for example. You’re going to hear complaints. You’re going to hear from politicians. You’re going to hear from advocacy groups saying there was an undercount. Or, “You didn’t count my neighborhood. What about this block. You said these houses are vacant. They’re not vacant!”

Rose: So let’s say that we do wind up seeing a really obvious undercount. And we start getting mayors and local officials and community organizers sounding the alarm to say that they haven’t been counted. Let’s say it’s enough people sounding enough alarms that it starts to look like the census just… isn’t accurate.

What next?

Well, nobody knows. Everybody I talked to basically just said… we’ll have to wait and see. There has never been a census that everybody can agree is totally inaccurate, at the time. We can look back and say, “Yeah, in 1940 that was an inaccurate census.” But at the time, they didn’t realize it.

The best anybody can come up with, in terms of a precedent, is the 1920 census.

The 1920 census was HEATED. The US in the 1920’s was still trying to recover from World War 1. The House and the Senate had both turned Republican and the president, Woodrow Wilson, struggled to maintain his sway. Workers were still trying to regain their lost wages from the war, and there were race riots in Chicago and Illinois. America was changing, demographically, and the 1920 census results reflected that..

Hansi: Census results came out, and the big headline out of that was that for the first time the U.S., based on the numbers, was no longer a rural nation. That there was big growth in the big cities. And that rubbed a lot of politicians, especially those in the south and from rural communities, rubbed them the wrong way. It was not in their best interests.

Rose: All these changes meant huge impacts on the way Congress was setup — nineteen different states stood to lose or gain seats because of the 1920 census. States with rapidly growing urban populations like California, Texas, Michigan and Ohio; they were all going to gain seats. States without any big urban centers, were going to lose seats. All told, the 1920 census was going to take away 11 house seats from ten rural states, and give them to eight urbanizing states. I say “was going to” because in 1920 both the house and the senate was controlled by the Republican party, who stood to lose in this reshuffling. And so they just… didn’t do it. They refused to reapportion Congress. They refused to acknowledge the results of the 1920 census.

Hansi: Some newspapers called it tyranny. Some people called it unconstitutional.

Rose: It took eight years for them to finally acknowledge the 1920 census numbers, and they eventually passed a bill to reshuffle the seats in January of 1929, just one year away from the next census.

But in 2020, simply ignoring the census actually isn’t an option. Because there are now laws on the books that say that the reapportionment of congress has to happen automatically. But the funding allocations, those are more of an open question. The government is going to have to decide whether it wants to just, go forth and use the 2020 numbers it knows are faulty, or maybe ignore those numbers entirely and wing it, or just… stick to 2010 numbers?

Susan: So you could have states which are getting much more than they’re entitled to, because they had a pretty full count. And then states which really need the assistance, and didn’t have a nearly accurate enough count, and they won’t get the resources that they’re entitled to.

Phil: The last thing you want is the national policymakers deciding their own priorities based on backroom deals. “My town and city deserves x number of dollars for Head Start. Give it to me based on my political power.” No. It’s based on census data which is nonpartisan and right there for everybody to see.

Rose: Now, many of you listening are technology savvy people. And you might be thinking: wait a minute. Google and Facebook and Apple, and all these technology companies are constantly gathering information about me all the time. They know where I live, what I eat, where I travel. Why can’t these big data brokers just give the US their data, and we can call it a day?

Well there are some issues with that plan.

Susan: The data which Google has is skewed to a certain population. You know, you fall right into the digital divide. You really can’t expect that a migrant population, or a homeless population, is going to be particularly accurately reflected by the sorts of information which Google collects online. That population’s barely online, if at all.

Rose: And even if you try to rely on, say, Google Street view, and say “okay well, I see that there are these apartments, which usually have this many people in them,” you’d wind up getting a really inaccurate count. This is something that Dawn experienced first hand when she was taking the census in 2010.

Dawn: I mean, there was literally… I would go to one place on Clinton Avenue, for example, which is a beautiful, beautiful street in Brooklyn. Has all kinds of brownstones, and so on this one block, I remember going to this one house where it was it was massive. It was it was four stories high. We walk in, and this woman, this white woman was like, “Oh you’re from the census, just come on in. Let me let me get you some treats.” She brought out some organic snacks. She brought out water and all these kinds of chips for us. So we’re just taking notes, a little poodle dog comes running over to lick our toes and whatnot. And so I was like, “This is beautiful how many people live here?” And she said, “Three.” And I said, “Three?” She said, “Yeah. Myself, my husband, and my daughter.” This is a four story house. Ok, a four story house.

And then, right next door, we would go and it would be a whole slew of apartments on each floor. Maybe not a slew of apartments, but maybe two apartments per floor, for a total of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. There was at least 16 people in the building right next door, that looked exactly the same to the other buildings.

Rose: So, Dawn told another story about her census experience on the podcast The Story Collider. At the end of her census taking, her partner, Eloise, turned to her and asked her a question. And It’s a really weird and surprising question. I don’t want to spoil the surprise for you, so you should go listen to that podcast once you’re done with this one. I will link to it in the show notes as well.

So when I asked Phil and Susan and Cayden if there is some kind of backup plan, some plan B is the census goes completely haywire in 2020, and they all basically said… no. This is it. We’ve got this one chance. And if we screw it up, we’re going to wind up in a really weird, tricky situation for the next ten years.

Cayden: Part of this, sort of like, both the promise and the like challenge of building democratic society is that you need to…. in some ways it assumes mass participation. But in order to perpetuate it, there needs to be mass participation. I guess for me the analysis is it’s just unacceptable to leave any community behind.

Rose: It’s sort of interesting — when I do science and technology futures, they’re actually usually easier to predict than political ones. The 2020 census is clearly having some problems, but what happens next is way harder to predict than, say, what might happen if facial recognition technology was ubiquitous. Or even what might happen if every volcano on earth erupted at once. For those futures, we can basically predict what would happen next. But for this one… nobody really knows. We can make some good guesses — roads and schools and school lunch programs would suffer, there would probably be some big lawsuits against the government by organizations like the NAACP. And there will certainly be a whole lot of fighting about it in the political arena.

We would probably still use the census data to ask questions about what to do, and what to fund, and where to build; but with a bad census, we might not get the right answers to those questions.

[[music up]]

That’s all for this episode. Which is the second to last episode of the season! In two weeks, you’ll hear the SEASON FINALE which is so exciting. It’s a fun one too.

Before we get to the credits, I promised you all a psalm, so here it is. This is the psalm that Tim Rosko, Nick Tiberi and Emily Swora recorded, based on the arrangement by Hamish Symington and Owain Park, based on the algorithm by Janelle Shane. Enjoy!

For thou art my God, O God:

I will observe thy statutes:

I will not reprove thee for thy sacrifices;

And my tongue will rejoice with my transgressions;

And thy testimonies be clothed with frogs;

The faithful was in the lands of the earth;

And the peoples he gave them the dust,

He sent them wonders of the dunghills of God.

And he brought forth his praise to pants.

Then they went up a highway for him that rideth through the mountains.

And the wild beasts of the seas;

And the wild beasts of the field of eat,

And the bars of the river of the river of thy wings.

And the cattle upon me, O God;

And the cattle upon the house of God, ye bread with thee.

Oh let them do no bungers in the mountains;

And the wild beasts of the field exult thee about the sheep of thine anger

Their heart shall be abundantly satisfied with frogs.

You’ll be able to find the lyrics to the psalm, and the arrangement if you are so inclined to sing it yourself, on our website, flashforwardpod.com. You’ll also find more links to all the things we talked about in this episode, along with more information about the interviewees you just heard from.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. Special thanks this week to Liz Neeley who voiced our future, very frustrated, bureaucrat. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! This episode was suggested by a listener, thank you so much. And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

28 comments

[…] https://www.flashforwardpod.com/2017/12/26/countless/ […]

I’m surprised you didn’t mention the 2016 Australian census, which was a bit of a disaster as it was the first census done online, the census website crashed straight away, and a lot of people (I mean, who knows how many people, it’s not like you can count them now), didn’t take part because some jerk decided that names would be forever linked to census information. It was quite a big deal at the time.

[…] away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] away hundreds of thousands of immigrants from filling out their necessary surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to find out congressional apportionment for the subsequent decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] hundreds of thousands of immigrants from filling out their obligatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s employed to establish congressional apportionment for the upcoming 10 years, allocate […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]

[…] could scare away millions of immigrants from filling out their mandatory surveys — throwing off the count of who’s present in America that’s used to determine congressional apportionment for the next decade, allocate federal […]