Today we travel to a future where humans can see at night. What happens when we expand our vision out into the darkness? How does that impact everything from work, to architecture, to poaching to horror movies? And is it even possible?

🚨 BECOME A PATRON BEFORE JUNE 30TH AND GET A SPECIAL REWARD! 🚨

Guests:

- Gang Han — researcher at UMass Medical School

- Gabriel Licina — researcher and “sometimes biohacker”

- Lynne MacTavish — operations manager at Mankwe Wildlife Reserve

- A. Roger Ekirch — historian at Virginia Tech and author of At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past

- Ernest Freeberg — historian at the University of Tennessee and author of The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America

Actors:

- Maria — Cara Rose de Fabio

- Gaby — Eler de Grey

- Marquis — Rotimi Agbabiaka (check out his new solo show called Manifesto on June 21 at the African American Arts and Culture Complex as part of the National Queer Arts Festival.)

- John — Keith Houston (also check out his karaoke nights in San Francisco)

Further Reading:

- UMMS scientists develop technology to give night vision to mammals

- Mammalian Near-Infrared Image Vision through Injectable and Self-Powered Retinal Nanoantennae

- Nanoparticles give mice night vision

- Chlorophyll derivatives as visual pigments for super vision in the red.

- The Real Science Behind the Crazy Night Vision Eyedrops

- Patent: Methods to enhance night vision and treatment of night blindness

- A Review on Night Enhancement Eyedrops Using Chlorin e6

- In Africa, technology is the final weapon in the deadly poaching war

- Conserving endangered rhinos in South Africa

- Can Handheld Thermal Imaging Technology Improve Detection of Poachers in African Bushveldt?

- At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past

- Ghosts in the ancient world

- Why Some People Never Grow Out of a Fear of the Dark

- Busting the 8-Hour Sleep Myth: Why You Should Wake Up in the Night

- The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America

- LINEMAN FEEKS’S DEATH.; WITNESSES DESCRIBE IT TO CORONER SCHULTZE AND A JURY. (New York Times Archive)

- FUNERAL OF THE VICTIM.; SERVICES OVER THE BODY OF LINEMAN FEEKS–HELP FOR HIS FAMILY (New York Times Archive)

- Are Shorter Work Hours Good for the Environment? A Comparison of U.S. and European Energy Consumption

- The Great Lightbulb Conspiracy

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Special thanks this episode to

Adria Otte and Molly Monihan at the Women’s Audio Mission, where all the intro scenes were recorded this season. Check out their work and mission at womensaudiomission.org.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹

Rose: Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! This is the first episode of a new mini-season, where I’m going to show you five different futures related to the theme of BODIES. You know, those squishy, meat sacks we all have. Sometimes they behave nicely, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes we like how they work, and sometimes we think they could use some improvements. Sometimes we have full control over them, and sometimes, they seem to have a mind of their own. As I record this, right now, I have this weird twitch in my right shoulder muscle, for example, which is very distracting and strange… and I can’t make it stop.

But anyway, what is this show? Who am I? What are we all doing here on this planet? I can only really answer two of those questions. I’m Rose! I’m your host, and I’m going to guide you through all these strange and surprising what if scenarios. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible… or not so possible future scenario. We always start with a little fictional field trip to the future, to check out what’s going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to real experts about how that world we just heard might actually go down. Got it? Great!

Before we go to the future, I want to tell you two more things! FIRST: There is new merch in the Flash Forward store! My personal favorite is this new t-shirt that says “Imagine Better Futures” but we also have pins, bags, and trophies, if you’ve ever wanted to give someone a “worst futurist” trophy, wow, now you can. You can find all that stuff at flashforwardpod.com/shop. If you do wind up getting Flash Forward stuff please send me pictures, it makes me ridiculously happy to see people wearing their Flash Forward merch, you really have no idea.

SECOND! I’m running a little bit of promotion on Patreon right now. So, as you might know, Flash Forward basically only exists because people donate money to the show on Patreon. And if you sign up to become a patron at any point during this little mini-season, so that’s from today, May 14th, through the end of June, let’s say, you get a present from me! I’ve got exclusive Patreon only stickers, zines that I illustrated about my favorite phrase, the future is now, and other cool surprises. So! If you’re not a patron, and you’ve been waiting for some kick in the butt to become one, this is me! Kicking your butt… gently… with presents! Go to patreon.com/flashforwardpod for more information!

Okay, on to the future! This episode we’re starting in the year 2029.

[knock on the door]

Gaby: Hey, Maria, what’s up.

Maria: Hey! Oh good, you’re here. Okay… John and Marquis said they’re on their way too.

Gaby: Cool… What are we doing exactly?

Maria: It’s a surprise. You’re not wearing contacts are you?

Gaby: No, I got your text, why?

Maria: I’ll explain when the guys get here.

John: Hello hello. You requested my presence. Hey Gaby.

Gaby: Hey.

John: What’s the deal?

Gaby: It’s a surprise apparently.

John: Cool I love surprises.

[awkward silence]

Maria: He said he’d be here like, any minute.

Gaby: Hey John did you hear about the marching band?

John: [guffaws] Yes

Maria: What happened?

Gaby: They got banned from all sporting events indefinitely.

Maria: Why?

Gaby: Something to do with a squirrel, or multiple squirrels?

John: Yeah

[Marquis enters]

Marquis: Hey sorry, I saw an ex on the way over here and I had to take an alternative route.

Gaby: [sarcastic] God forbid she see you.

Marquis: Yeah, would have been bad. Then I got kinda lost. Still don’t totally know how to get over here from my place exactly. But … what’s up? I hear there is a surprise.

Maria: [excited] Yes! Okay… [conspiratorially] So… I’ve been interning at this lab. My job is, honestly, very boring BUT the research they do in the lab is super cool. They’re looking at applications of nanoparticles on night vision in rats. So, normally what we do, well, they don’t let me do it, but normally what the grad students do is inject these particles into the rats eyeballs with these really long needles.

Gaby: Jesus.

John: Maria…

Maria: Let me finish! [talking quickly] The reason they do that is because it’s really hard to get the nanoparticles to penetrate the cornea and get to the photoreceptors at the back of the eye. But… I think I figured out a way. And… I made these eye drops.

[pauses, nobody reacts]

Maria: They can make you see at night.

John: No way.

Gaby: Absolutely not.

Maria: Listen… I know they work. I’ve tried them on myself several times.

Marquis: What if we go blind?

Maria: You won’t go blind. I promise. I have not gone blind yet.

Gaby: What if you go blind SLOWLY. You could be going blind right now!

Maria: I’m not. I’ve been testing my vision every day for months.

Marquis: And they make you see at night?

Maria: Yeah.

Marquis: … I’ll try it.

Gaby: Are you kidding me?

John: Does it hurt?

Maria: No. It just feels weird, to work they kind of numb your eyeball a tiny bit for a few seconds.

Gaby: Oh that’s great! That sounds totally safe.

Maria: [interrupting] But it goes away, and again, no long term side effects.

Gaby: That you’ve seen YET.

John: How long does the night vision last?

Maria: About a week?

John: A week! A week of night vision? Cool! How good is it though, like how much can you actually see?

Maria: On me, really good. But that’s why I want to test it on you… I don’t know how sensitive other people’s photoreceptors are to this stuff.

[pause]

John: … okay, yeah, sure. Why not.

Gaby: Oh my god! You’re all idiots.

Maria: Hey, we might be foolish but we’re not idiots. If you’re not going to do it, that’s fine, but you should still come with us.

Marquis: Where are we doing?

Maria: Well you can’t test night vision drops in the middle of a dorm room can you? We’ll do the drops here and then walk out into the woods.

Gaby: Very safe! Yeah, what could go wrong!?

Maria: You don’t have to do it, jeez, we get it. I already did my drops before you got here. So, we’ll do you guys one at a time I guess. Who wants to go first?

[silence]

Marquis: Okay fine I will.

Maria: Cool so lay on this beanbag, kinda get… horizontal I guess. So I can drop them into your eyes.

Marquis: Oh you’re gonna do it?

Maria: Yeah I think that makes the most sense.

[getting situated]

Marquis: Okay, okay, so… like this.

Maria: Yeah, now, take your fingers and hold your right eye open for me… I’m just going to drop them in, and even when I stop dropping keep your eye held open for a couple seconds.

Marquis: Ooh! Cold!

Maria: Keep your eye held open…. Okay, now we can switch. Left eye, same deal.

Marquis: Okay…

Maria: All right, that’s it. Don’t squeeze your eyes together, try and blink gently, you don’t want to flush out the drops.

Marquis: Okay…

Maria: How do you feel?

Marquis: Yeah it does feel kinda weird… but I don’t know if I would have noticed if you hadn’t told me to expect something?

Maria: Great! Okay John, your turn. Same deal.

John: Got it!

Maria: Ready?

John: Yep! Gimme that super power!

Maria: [laughing] okay, 1..2…3…4 right eye. Hold it open for a couple seconds. Okay now left eye… 1…2…3…4. Don’t blink. And… you’re good.

Okay, so, how do you guys feel?

John: … fine? The same?

Marquis: Yeah, nothing to report.

Maria: Nothing looks any different than it did before right?

Marquis: Nope, same as always.

Maria: Okay great. [excited] Ready to go into the woods?

John: Yeah! This should be fun.

Gaby: I’m coming with you, and I’m bringing a flashlight so you don’t get lost.

Maria: Okay but you can’t turn it on unless we really need it, otherwise you’ll ruin the effect. And we’re not going to get lost.

Gaby: [sarcastic] Right, superpowers, got it.

[hear them leaving the dorm, walking out]

Maria: This is where the cross country team runs, so I know it pretty well. This path will take us up and over a little ridge and on the other side we’re pretty well blocked off from the light pollution from campus.

Marquis: Cool.

Maria: Do you guys mind if I record this? For my notes? I want you to describe what you’re seeing, just, I guess kind of stream of consciousness, tell me everything.

Marquis: I guess that’s fine… just don’t put it online or whatever.

John: I don’t care.

Maria: Yeah just for me… okay… I’m recording.

[sound changes to Maria’s recording]

[sound of walking through the woods]

Marquis: It’s kind of hard to tell… if it’s working? Like I don’t think I’ve ever been out here before.

John: I think I can kinda see better? But yeah, I don’t really know.

Gaby: I can see just fine, so…

Maria: Wait until we get to the ridge, then we can go off the trail and into the actual darkness.

[more footsteps, breathing, everybody is slightly out of breath]

Maria: Okay, this is the top. The trail goes right, but let’s go left, we can get under the tree cover and you’ll be able to tell better I think.

John: I can already definitely tell — I can see rocks over there, and there’s a lighter on the ground right here.

[walking]

Marquis: Whoa

Maria: What.

Marquis: I think I just like, got it. Realized what this actually is doing to my eyes. It’s not like it’s daylight or anything. But I can see — I can see the trees, the bark on the trees, where the stumps are, where you’ve walked. You look kind of … reddish I guess? Like you’re glowing.

Maria: Yeah, every body gives off infrared heat, which you’re going to be able to pick up.

[tripping sound]

Maria: Gaby? You okay?

Gaby: It’s really dark.

Maria: Yeah… and you can’t see anything can you?

Gaby: … Not really…

Maria: [getting excited] Actually, this is great. You’re our control!

Gaby: Lucky me!

Maria: Can you see the tree to my right?

Gaby: … sort of… the outline?

Maria: And what about the stump to my left?

Gaby: What stump? No… I guess the answer is no.

Maria: John, Marquis, can you see them?

Marquis: Yeah… totally.

John: [excited now] Yeah… yeah! I can see that, and the mushrooms creeping up that tree there, and the vines that are connecting those two branches. I could run through this forest and not trip and fall, I can see all the rocks and roots and everything! This is… this is incredible.

Maria: [proud] I know. I think it could be… really big.

John: Totally… man… what do you think like, early humans would have thought of this? You know? Like cavemen? They had to fear the dark because there were lions… but we don’t anymore… this is it. Like… Batman no longer owns the dark… WE DO.

Marquis: [making Bane voice] You merely adopted the dark. I was born in it.

John: [laughing] Totally dude… totally.

Gaby: Can we go? You might be able to see… but I can’t… and I’m cold and … honestly kind of scared.

Marquis: You said this lasts weeks?

Maria: On me, yeah, and in the mice.

John: I’m gonna come out here every night.

Marquis: Let’s meet again tomorrow dude!

John: Hell yeah.

Maria: Please don’t do anything stupid.

Gaby: Guys… can we go?!

Marquis: Yeah, yeah, for sure, Gaby you want a piggyback ride?

Gaby: …. Yeah actually that sounds great. I can’t see ANYTHING and I’m probably going to fall on my face.

Marquis: Hop on little lady!

John: Giddy up!

[walking out of the woods / fade out.]

[INTRO SCENE]

Rose: Okay! So today we’re headed to a future where humans can see at night. Night vision! This is a superpower that shows up in a lot of science fiction, whether as someone’s main power, or just one of the many things they can do. Wolverine can see at night, Venom can see at night, in some Spiderman comics, Peter Parker can see at night. Nightcrawler can, obviously, see at night. There’s also Riddick, from the Chronicles of Riddick:

Jack: Where the hell can I get eyes like that?

Riddick: Gotta kill a few people.

Jack: Kay, I can do it.

Riddick: Then you got to get sent to a slam, where they tell you you’ll never see daylight again. You dig up a doctor, and you pay him 20 menthol Kools to do a surgical shine job on your eyeballs.

Jack: So you can see who’s sneaking up on you in the dark?

Riddick: Exactly.

Jack: Leave.

Rose: And it’s pretty easy to understand why this might show up in a ton of sci-fi and fantasy. First, it’s a really cool thing to be able to do. To be able to see at night is also incredibly useful if you’re trying to sneak around and do stuff you’re maybe not supposed to be doing, possibly wearing some kind of weird superhero latex costume that may or may not involve a cape.

Humans — non super hero humans — can’t see at night because our eyes aren’t designed to do so. The photoreceptors inside our eyeballs can only really pick up and understand light that falls between 400 and 700 nanometers, that’s the range we consider visible light for humans. When we’re talking about night vision, that means we’re trying to be able to push our vision out beyond 700 nanometers, what are called near infrared wavelengths.

You’ve probably seen night vision footage that detects infrared wavelengths — it’s that footage where it’s picking up basically the body heat of animals out there. So maybe you’ve seen deer on infrared cameras, or even people, where they’re like these strange, glowing, lava monster looking figures moving around. Those cameras are picking up the infrared signals that the boyd gives off.

And this is actually one of the reasons humans can’t see infrared. We’re warm blooded, right? And anything that gives off heat, is giving off infrared light as well. And that is true inside our eyeballs too, where those photoreceptors are. So if we had really good sensitivity for infrared built in, we’d be seeing our own eyeballs all the time. The call is coming from inside the house!

Gang Han: That’s something you may notice. So when you close your eyelids, it’s not completely dark for you, right?.

Rose [on the phone]: Yeah. It’s like reddish.

Gang: Yeah. You see some green stuff, right? And sometimes you see some blinking stuff there, right? So this is not complete dark. That’s because you see the heat

Rose: This is Gang Han, a researcher at UMass Medical School. And Gang is one of the people on a team that recently figured out a way around this biological limitation, and gave mice night vision super powers. They did this by injecting mice with a specifically designed nanoparticle.

First, they thought they could just inject this nanoparticle into the mice’s eyeballs and be done with it.

Gang: Actually that’s wrong. The problem that we had after injection; we found that the particle aggregates there, then making trouble for eyes.

Rose: So they would inject the mice and the nanoparticles would clump together, instead of finding its way to the photoreceptors in the eye, where the researchers wanted them to go. This was bad because it meant the night vision didn’t work, and it also caused problems for the mice who now had clumps of stuff in the backs of their eyeballs. Okay, so plan B was to attach the nanoparticles to specially modified proteins.

Gang: The protein really acts as a glue. And glues a particle tightly on the photoreceptor.

Rose: And this worked — they attached these nanoparticles to proteins; they injected that new solution into the mice’s eyes; and the protein plus nanoparticle mixture stuck in an even layer on the photoreceptors. And it stuck for a lot longer than Gang expected.

Gang: It’s a good surprise to me. After we inject particle into the eye, we actually did this test after 10 weeks.

Rose: Ten weeks! And, most importantly, the injection did what they hoped it would do. It gave the mice night vision. And they tested this in a couple of different ways. The first was to just shine a light into their eyes, and see what happened. As you probably know, the pupil in your eye, that black bit in the middle, expands and contracts depending on how much light there is.

So they shone infrared light into the eyes of these mice. And in the mice without the nanoparticles, their pupils did nothing. They were not picking up any light. But in mice with the nanoparticles, their pupils shrank, which indicates that they did indeed sense the presence of this light. Great. Check. Step one. That’s the simplest test.

But they wanted to know more, like how good is this vision? It’s one thing to see an involuntary reaction, like a pupil getting smaller, but can the mice actually process the light, does their conscious brain see it? And can it do anything with that information? Which leads us to experiment number two.

Gang: So basically we made two boxes that connect together with a doorway. So, one box is in complete dark. The other box is actually wrapped with this near infrared light.

Rose: You probably have experience with this. Mice tend to want to stay in darker areas, right? They like to scurry around in places they can’t be seen as easily.

Gang: The mice without part of the injection, and basically the near infrared box is dark to them too. So they stay in both blocks equal time.

Rose: But the mice with the injection, they avoided that box with the infrared light, because they could see it. It was brighter to them. Okay, so the mice can see the light, and they can use that information somehow. But Gang and his team wanted to know more, so they set up a third, even more complicated experiment.

Here’s how it goes: You have a long tank of water, and at the end of the tank there are two little screens. In front of one screen, is a hidden platform. Mice don’t like to be in water, so when you put them in the tank, they’re going to swim and scramble and try to find their way out. So they have an incentive to learn where this hidden platform is, so they can stand on it, and keep their head above water.

Now, on these screens at the end of the tank, the researchers put different patterns like a circle or a triangle, illuminated with infrared light. And for each mouse they tested, the hidden platform was always in front of the screen with the same shape, whether that’s a circle or a triangle. It was always the same for that mouse.

Gang: So, actually, mice with the particle injection can tell the difference. If different shapes then go to the right target, very precisely each time. But mice without the particle injection; for them it’s complete dark. So they’re just lost.

Rose: So not only can the superhero night vision mice see this light, they can see it well enough to detect these shapes, and be like “oh, triangle, that’s what I want, that’s where my little platform is going to be.” Meanwhile, their poor comrades are swimming around in the dark, with no clue where they’re going or what is going on.

Side note: there is some research to suggest that mice and rats can communicate with one another in the lab. And remember this night vision lasts for at least ten weeks — so I kind of wonder if these mice go back into their cages at night and are, “you guys are not going to believe this but I can totally see now, at night.” And the non superhero mice are like, “yeeaaaahhhh sure you can Brad.” Or maybe they’re jealous that they didn’t get picked to get super powers. Maybe there’s infighting between the two groups — like Mean Girls, but … with super vision mice.

[Clip from Pinky and the Brain]

Pinky: Gee Brain, what do you want to do tonight?

The Brain: Same thing we do every night, Pinky. Try to take over the world.

Rose: Anyway, right, back to Gang’s research. So the next question here is… would this work in humans? Just because something works in mice doesn’t necessarily mean that it will work on us.

Gang: Actually, it could be applicable to a human. The difference from the mice’s photoreceptor and a human’s just is the number of the cones and the rods.

Rose: Mice have about 5 million rods and 150,000 cones. Humans have 120 million rods, and 6 million cones. But other than that number and the scale of what’s going on here, Gang says there’s not that much of a difference between human and mouse photoreceptors. But to test something like this in humans is really hard. And really expensive. The nanoparticles that Gang is using are not FDA approved. So now they’re going to actually trying to see if they can do the same thing with particles that are already used in other applications. So other people have already gone through all the FDA hoops for them.

Until then, however, trying this on people is purely in the realm of those who are willing to circumvent the rules.

Gang: I get some, like, funky e-mails every day. There’s some biohackers, I guess.

Rose: Ah yes, biohackers. And when I first heard about Gang’s research, back in February, I immediately thought of one biohacker in particular.

Gabriel Licina: And then the night vision eye drop thing happened. And for those of you who can’t see video, I’m making jazz hands.

Rose [on the phone]: Your claim to fame, sort of, on the internet!

Gabe: [exhales] Well, yeah, whatever.

Rose: This is Gabriel Licina

Gabe: I’m a research scientist, and sometimes bio hacker.

Rose: And I thought of Gabe because, in 2015, he did a night vision body hacking project using a chemical called Chlorin e6, or Ce6. Which is what’s called a chlorophyll analogue. You might remember chlorophyll from high school biology — it’s the stuff that makes plants green. Chlorophyll is a pigment, and what it does for plants is absorb light, that they can then use to turn into energy. Chlorophyll is the best at absorbing blue and red light, including red light that our eyes can’t normally see. Light that is outside the visible spectrum. But chlorophyll, and these chlorophyll analogues like Ce6, aren’t just found in plants. They’re also found in deep sea fishes.

Gabe: And they consume random green stuff, and some of this chlorophyll analog makes it to their eyes and it bonds to the opsin protein.

Rose: The opsin protein is one of the main light sensitive molecules in the eye. And researchers think that having this green chlorophyll pigment bonded to that light receptor helps these deep sea fishes see in the very deep, very dark ocean.

Gabe: So imagine these molecules kind of floating around in your eye, just kind of booping things in to the area that you can see. And actually that’s the whole hack right there.

Rose: But does it work on people? That’s what Gabe wanted to find out. And he had a few things to work from: some papers about these deep sea fish, one study on applying Ce6 to mice, and a patent filed by a shady dude who lost his medical license to fraud in 2008. At the time, Gabe was working with a guy named Jeff Tibbetts. And while Gabe was always confident that they’d be able to figure this out, Jeff.. was not.

Gabe: Jeff was kind of under the impression that I was going to lose my eyes, actually. He came home, once and he was just really upset. And he was just like, “You’re going to ….somebody is going to lose their eye because of this.” And I’m like, “No man. The research is solid,” and he’s like, “What about this. Why is this there?” And I’m like, “Well I haven’t figured that out yet. And that’s why I’m not doing it.” You know, and then we actually figured it out. And then I came in and I was like, “Look at this paper. This is why it works.” And he was like, “You found it.” And I’m like, “I found it.” He’s like, “OK.” And that was it. There was no doubt that it was going into my face.

Rose [on the phone]: Were you worried at all?

Gabe: No, I’m a professional, dude. I might dress like a slob, but I do know how to read.

Rose: So here’s how the experiment worked. The eye is really good at making sure stuff doesn’t get into the back of your eyeball, which in general is a good thing. So Gabe had to try and get these eye drops into the eye another way, via a vein that runs along his lower eyelid. And to do that, he had to make sure he did not blink the solution out of his eyes.

Gabe: So, step one was we pinned my eyes open. Clockwork Orange style.

Rose: Was this painful? Yes, it turns out pinning your eyes open with what looks like a torture device is just as uncomfortable as it seems.

Gabe: And then we measured it out precisely, and we used a micropipette to apply it to my eyes. There was this splash of very dark green and then it cleared up very quickly.

Rose: Then they quickly had him put on some dark contact lenses, and sunglasses, as a safety precaution.

Gabe: I had data that let me feel comfortable about putting it in my eyes. I didn’t have data about how well it would work. You can’t ask, “So, Mr. Mouse, how bright is the light right now?” And so, we didn’t really know if it was going to be crazy bright, or kind of bright, or not work at all. And so we decided to to err on the side of caution, which everybody should do. Please err on the side of caution. Don’t burn your eyes out.

Rose: So, contacts and sunglasses on, experimental eye drops in and, in theory, coursing their way through Gabe’s bloodstream, hopefully making their way to the back of his eyeballs where the photoreceptors are. Next step is they head out into the woods. And in the woods, they did a handful of tests: read letters of a closeline. Play hide and seek. Try and read playing cards in the dark.

They also tried to gather quantitative data using a machine called an electroretinogram, which is basically a device that measures the electrical activity of the retina.

Gabe: Unfortunately, because we were doing this all DIY science, we had a DIY ERG and it was just super noisy. We couldn’t get any real good data on it.

Rose: But anecdotally, Gabe says, that he definitely noticed a difference.

Gabe: It wasn’t magical, wonderful, Riddick vision. But it was more like just enhanced low light vision.

You know when you’re walking in a forest, and it’s pitch black, and you’re getting hit in the face with sticks over and over and over again, and you’re tripping on things? Like, that’s normal. You know when you’re walking in the forest, and the moon is out, and you’re ducking under the thing? You can actually see the trail, and you’re kind of not getting hit in the face? That’s what it was like. You know, I tripped less. I just didn’t smack my face so many times.

Rose: So, the project is a sort of success, they got some interesting data, learned a little bit about how this might work, and saw some preliminary results. What Gabe wasn’t expecting, was what happened next.

Gabe: Rich Lee is responsible for all of this, because he just took a picture while we were doing all of this and threw it on Facebook

Rose: The photo Gabe is talking about is a close shot of his face, where he’s looking at the camera. And it’s… really creepy. He’s got those black contact lenses in, that we talked about. His eyes are kind of swollen and red from the clamps that they used to keep them open while administering the drops. And it’s just… it’s a very striking image. And because it’s such a striking image, it totally took off.

Gabe: And I was just sitting there going, “I wasn’t done yet. I don’t have any good…. Oh God.” And then it just happened.

Rose: Gabe started getting phone calls from journalists all over the world. He did interview after interview after interview. And that photo, the one with his black eyes, was everywhere. And for Gabe, a lot of the coverage of this stuff, it was frustrating. His experiment was done on no budget, with limited tools. It was meant as a beginning, and it was being treated by the media as an end — the culmination of something wild and exciting and risky and incredible. The future is now! The headlines said.

Gabe: Every single time something comes out, and then someone’s like this is it: Mind uploading is happening now! I saw Elon smoking a blunt and we are going to the future on an underground train to Mars! And it’s like, that’s not how any of this works at all.

Rose: Doing actual research on this stuff costs money, and Gabe and Jeff didn’t even have enough money to get some of the data they wanted in this initial experiment. And despite all the attention, no more funding came out of the woodwork for them to continue and try to get better data. Instead, what Gabe got were desperate emails.

Gabe: I was getting a dozen emails every day from people that were like, “Our daughter, who is 9 years old, is going night blind. She’s got R.P. Will you please… How much do we need to to to send you? How much money to buy this thing?” I’m like, “I am not selling you, or giving you for free, experimental chemicals for your 9 year old daughter.” This is… what is going on? And it was really emotionally stressful, actually.

Rose [on the phone]: Did you respond to them?

Gabe: I did. I responded to every single one

Rose [on the phone]: What do you say?

Gabe: I’m sorry. I’m sorry, this was something that the media got excited about. But I don’t think it’s safe. And it’s definitely not a product. And I can’t sell it to you. And I can’t give it to you. And I’m very sorry. And none of these people replied back. Which is good, because if they came back, it would have been so terrifying. I don’t know how I would have dealt with that. It’s so sad. There’s just so many unhappy people out there.I don’t know how to appropriately talk about this.

Rose: I’ve been thinking a lot about why Gabe’s project got so much attention. I think a huge part of it was that photo, obviously — which I’ll post on the Flash Forward blog post to go with this episode. But I think the other reason this totally blew up, is because this is a superpower that we’ve all kind of wished for at some point, right? We’ve all kind of had that experience where it’s dark, and we can’t see. And, crucially, it feels way more attainable than other super powers. We kind of know that we’re never going to get bit by a radioactive spider, or develop super strength or suddenly being able to fly, or morph into animals, or flit between dimensions. But night vision feels like a power we could actually give ourselves, right? We have eyes, we know some animals can see in the dark, so… why not us?

We don’t know if Gang’s nanoparticle method will work in humans. And we don’t know if Gabe’s eye drops will ever get more funding or development. And even if these techniques do work, we don’t know if the FDA will approve them. It’s still unclear what the side effects might be in the long term.

But let’s say that, FDA approval or not, this works in people. And people start using it. What happens next? Humans have already deeply shifted our relationship with darkness over our 200,000 ish years on the planet. We tamed fire in part to tame darkness. We organize our days around the dark, the dark is where cultural myths and legends are born. And we’ve invented countless gadgets and devices to pry more and more time and space away from the clutches of night. And when we come back, we’re going to talk about what might happen if we completely upend our relationship with the dark. But first, a quick word from our sponsors.

[AD BREAK]

Rose: Okay, so it might actually be possible to give humans night vision. And I think this is… a big deal. Now, some of you might be thinking like “wait a minute, Rose, you know there are already night vision cameras and goggles right? And… flashlights exist. So how different would this really be?” And yeah, sure, night vision goggles exist, and they’ve totally have had an impact on things like war and animal conservation.

In fact, right now, on game reserves all over Africa, there’s kind of an arms race going on between poachers and conservationists, when it comes to night vision technology. And to hear more about that I called Lynn MacTavish, who helps run the Mankwe Wildlife Reserve, and if you want to hear that interview, become a Patron! In this week’s BONUS episode you’ll hear all about poaching, rhinos, and how night vision might tip the scales on a game reserve.

But I think that there’s sort of a key distinction between night vision goggles, like the ones that Lynn uses, and having actual night vision in your body. Goggles require power and batteries, they have technical limitations, they’re unwieldy. Night vision, something that exists within you, as part of your built in abilities, that’s… sort of something else? Night vision goggles let you do something specific at night. Night vision, lets you … be in the night. It means that darkness is no longer a limitation, in general. And that, I think, isn’t just a questions of technology, it’s a thing that has philosophical implications. Darkness is more than just the literal absence of light. Darkness has cultural baggage, it has weight to it — I mean we say that night descends, darkness falls. The night is where the scary things happen, the dark hides all the things we’re afraid of. The Talmud says: “Never greet a stranger in the night, for he may be a demon.”

[camp fire sounds and creepy music]

Narrator: We’re called The Midnight Society. Separately, we’re very different. We like different things, we go to different schools, and we have different friends. But one thing draws us together: the dark. Each week, we gather round this fire, to share our fears, and our strange and scary tales. It’s what got us together, and it’s what keeps bringing us back. This is a warning to all who join us: you’re going to leave the comfort of the light, and step into the world of the supernatural.

Roger Ekirch: There is no doubt that by the time of virtually every ancient civilization, widespread fears of the dark existed.

Rose: This is Roger Ekirch, a historian at Virginia Tech, and the author of a book called At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past.

Roger worked on At Day’s Close for twenty years, and you can totally tell, the book is full of examples and anecdotes of all of the ways the Western World has thought about darkness and nighttime through history. And in general, night time has been terrifying. In Greek mythology, Nyx was goddess of “all-subduing” night. Her children are disease, strife, and doom. Ancient Romans told stories of the strix, a night flying witch that ate the entrails of babies. In Christianity, god is seen as light, literally, he’s depicted as a ray of light a lot of the time. The opposite, the devil, lives in the darkness, and God Fearing Christians know all about “the valley of the shadow of death.” For thousands of years, humans have been telling scary stories about the dark.

Roger: People told ghost stories, for the most part, because they believed them. And they were, especially adults, telling them to children… they were trying to instruct them in where to go, where to avoid, what to do should they be lost at night. There was a very practical purpose to the telling of such stories. It was a way it was a way for adults to control their children, at least at night. Have them go to bed at a decent hour, and avoid going outside unless absolutely necessary.

Rose: And this tactic was important, in part, because the night was really dangerous for both kids and adults. Imagine, for example, 16th century Europe. Most people don’t live in cities, where there might be some lamps around. Walking around at night could mean falling into a river, or a well, or a hole. And in cities it was practically dangerous too, because night usually meant lanterns which meant fire.

Roger: Fire was the greatest of all. It was the rare city that was spared a major, major fire at some point in its early modern life.

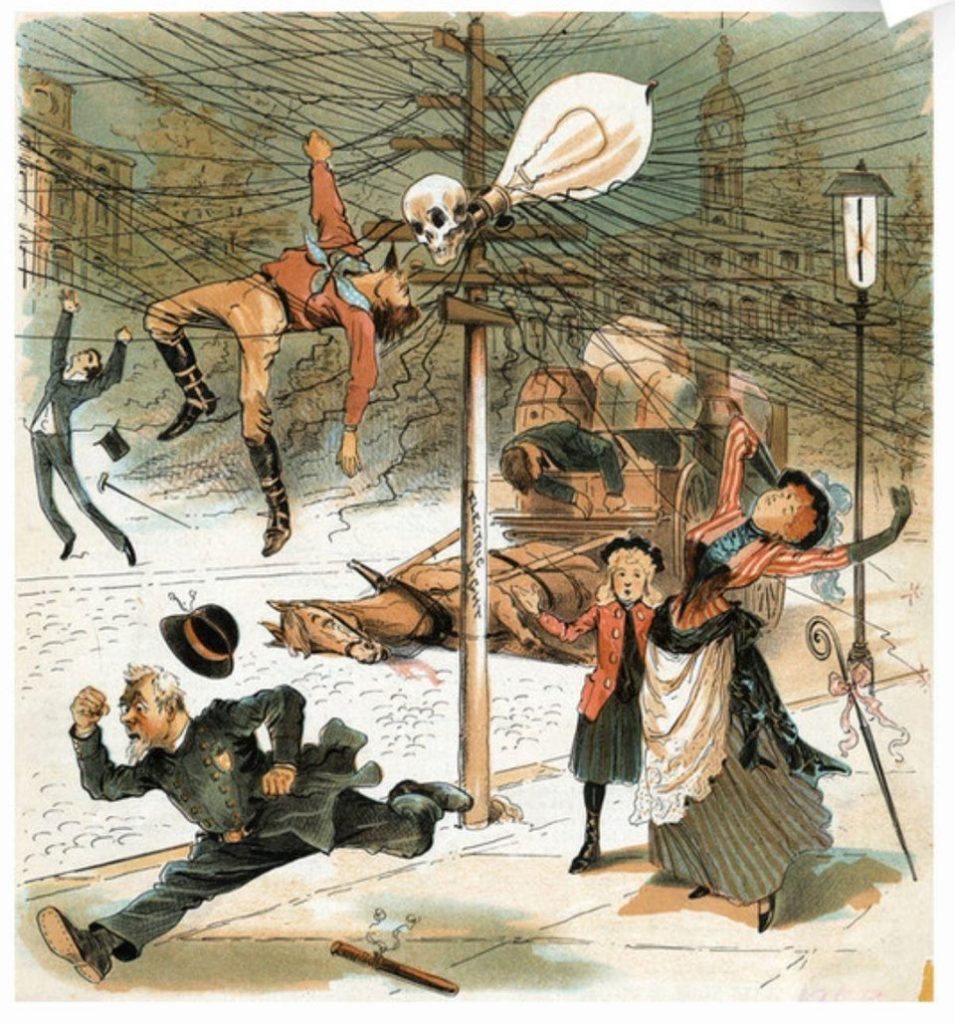

Rose: There’s an incredible engraving that Roger includes in his book

Roger: That’s the engraving, I believe, by William Hogarth, entitled Night.

Rose: In the image, there are two women trying to make their way through a dark, London street, and it’s complete chaos. There’s a fire in the street, one of the women is holding a sword to protect herself, there are people knocking over carts and generally running amok.

Roger: Including a gentleman on the second floor of the building in which he resided, emptying his chamber pot upon pedestrians on the street. It’s a wonderful, wonderful engraving, and not not altogether exaggerated, either.

Rose: Now, it’s not like people never went outside in the dark before flashlights. They obviously did. In fact, in some ways the darkness forced them to have a better understanding of the land than most of us do, because they had to.

Rose: Virtually every child committed to his or her mental memory, before they reached the age of maturity, a map of the village, or town, or urban neighborhood, in which they resided. They knew what spots to avoid, be it a churchyard cemetery, or a pond frequent hid by ghosts, allegedly.

Rose: And before the rise of artificial lighting, people were out in the dark, in part because people slept differently. Today, we try to pack all eight hours into one big chunk. But in the past, people broke their sleep into two parts.

Roger: Up until the mid to late 19th century, the dominant pattern of sleep in Western households, arguably is since time immemorial, or at least of Homer’s Odyssey, was segmented, or as some sleep scientists refer, biphasic.

Rose: So they’d go to sleep around 9 or 10 pm. And then around 2am they’d wake up, and they’d stay awake. There were prayers written specifically for this time of night. People would go to the bathroom, and do chores in the house that didn’t require a ton of light.

Roger: But then some, as well, left their beds to travel outside, visit neighbors, or even pilfer from a neighbour’s peach orchard. It was a prime time, in fact, for petty crime of all sorts.

Rose: And then they’d go back to bed and sleep until dawn. In fact, today, a lot of people are diagnosed with a sleep disorder called middle of the night insomnia. But Roger says that maybe, at least for some of those people, it’s not a sleep disorder at all. It’s a remnant of the way we used to sleep up until relatively recently.

But then, things changed. And they changed for a lot of reasons, but one of the big ones, is that we were able to illuminate the darkness, and see.

Ernest Freeberg: Well, there’s a long history of people looking for better and better forms of lighting. You know, the sperm whale just about went extinct as the search for whale oil. Kerosene replaced that. There was gas in urban environments. All of those things were a quest for more and more light in the 19th century.

Rose: This is Ernest Freeberg, the author of a book called The Age of Edison, which chronicles not just the invention of the light bulb, but the ways it changed the world.

Ernest: Electric light was just a culmination of a lot of different efforts to provide more light that had started a hundred years earlier.

Rose: In the years before the light bulb, people were using these gas lamps.

Ernest: People were so desperate, they valued light so much, that they put up with noxious fumes that would rot the furniture and give people enormous headaches. You know, the gas lines were very intrusive. Explosions were a problem. People were being asphyxiated.

Rose: So when Edison unveiled his version of the light bulb in 1879, people were really excited to have something that they could use inside that didn’t literally poison them. It took some refining, of course, from those early designs, but pretty quickly the lightbulb changed everything from architecture to surgery.

Ernest: Surgeons used to have to have a northern exposure; the right kind of skylight to operate under. They would use candles and mirrors and try to bounce light into the cavities of the body as they’re operating on them. An electric light was immediately transformative, as they developed tiny little, incandescent, pea sized bulbs to go along with the instruments. I think my favorite was the person who had people swallow a light bulb, and then would turn it on in order to see if the light would come through the skin in order to identify any any tumors or imperfections inside the body.

Rose: Hunters started using electric lights to spook deer. When cities started electrifying there were reports of mass numbers of birds getting confused by the lights and flying into the wires. Electric lights also led to better microscopes, which in turn led to a huge number of scientific discoveries. Light revolutionized art and photography. Suddenly, everybody from restaurant owners to theater directors had a huge new palette to work from.

Ernest: There were extravagant Broadway plays using washes of electric light, colored light, especially. So they began to realize that there was a light for romance, and there’s the light for study. And there’s the light for excitement and downtown nightlife.

Rose: Architects started to think about how their buildings would look at night, lit up. A building couldn’t just look good during the day anymore, it also had to have a pleasing nighttime aesthetic. The Pan-American Exposition in 1901 featured an Electric Light Tower that was covered in lights so it would look beautiful at night — a technique some people called “nocturnal architecture.” And it was really impressive, visitors said things like “it shines like diamonds!” and “It’s like a transparent soft structure of sunlight held stationary against the background of darkness.” Today, if you ever fly into a city at night, you will almost certainly spot at least one example of nocturnal architecture, buildings designed and lit in a specific way to look cool at night.

Electric light changed the way that cities and towns look forever. And not just because they’re now lit up, but because they’re also now covered in wires to carry the electricity to light them up.

Ernest: One thing that is invisible to us now, I think, or surprisingly invisible to us that wasn’t back then, is just how incredibly ugly the infrastructure is of electric lights and wires. Why should we trade a beautiful illuminated night for an incredibly ugly day, with all of these wires?

Rose: Before the lightbulb, most people’s homes didn’t have electricity running to them. But when electric lights hit the market, everybody wanted them in their homes, and people had to figure out how to get power to those bulbs. And in the early days of electrifying the city, it was a total nightmare. There was almost no regulation over these power companies, and they were stringing up wires everywhere with no insulation, no order. There were telephone poles just piled on with seemingly random wiring. And it was really dangerous.

It actually took a series of really public, and gruesome accidents for this to change. In 1889 some overheated electrical wires sparked a fire in Boston that burned down most of the city’s business district. And just a month before that, New York City had its own incident.

Ernest: Well John Feeks was just one of many linemen. This was a kind of a pioneering industry, to be up there above the city streets messing with this huge array of wires.

Rose: Feeks had been told that all the wires on the pole he was working on were dead. But it turned out at least one of them wasn’t. And he touched it.

Ernest: And he basically fried alive, and then dead, over the crowd in downtown New York, near the City Hall building. A big crowd gathered to watch as flames were leaping out of his mouth and they finally managed to figure out how to turn off the wires and get him down there.

Rose: I’m just going to repeat that; Feeks died instantly from the shock, but he shot fire out of his dead body for over a half an hour, while onlookers gathered on the street.

Ernest: And that really became a cause for New York to finally say enough is enough. These companies are too dangerous.

Rose: In the case of Feeks, no one company was ever convicted, because the mass of wires on the poll was impossible to untangle, and they couldn’t actually figure out who was at fault. After the trial, the mayor of New York City stepped in.

Ernest: They actually started to take electric wires down, a number of places got plunged into darkness, forcing the electric companies to to clean up and straighten out their wires before they could go back up.

Rose: But New Yorkers weren’t happy with this solution either. They had, literally, seen the light. They didn’t want to go back to darkness, or to their smelly oil lamps. They wanted electric lights. And to give them lights, cities around the country took a page out of what was basically a science fiction novel. In 1888, a year before John Feeks fried on a telephone line in New York City, an author named Edward Bellamy published a novel called Looking Backward, 2000-1887. The book paints a utopian future, and one of the many things that makes it a utopia, is that the government controls utilities.

Ernest: So many progressive reformers, following Bellamy’s idea, suggested this is really something that that ought to be treated as a public utility.

Rose: Today, in the US, we obviously don’t have a totally public system for electricity, but providers are still required to answer to governments way more than they were in the 1880’s. The point of this story, is that the way our electricity is regulated today was shaped, in some part, by the demand for electric lights. And the demand for electric lights comes from our long battle with darkness, which only exists, because we can’t see at night.

So, in this future, where we can see at night… what happens? I don’t think electric lights go away, even if we can see at night. History isn’t something that we can just reverse — we can’t scrub along the timeline and go back to before the lightbulb was invented. Although I do think that there might be communities that decide to “go dark” so to speak, for environmental reasons. Lighting accounts for about 15 percent of global electricity consumption, so finding ways to cut that back would be good for the planet. But that would be the exception to the rule, I think.

And that’s in part because, lighting is more than just functional, right? Lighting does something for us, it creates a space and a mood and a feeling.

Ernest: Electric light doesn’t simply give us the ability to see at night. It shapes our perception of various things. There is the light of the exciting downtown centre. And there’s the mood light of a reading room. And the kind of light that we see in a hospital that signals to us that the place is clean, and safe, and sanitary. Think about how exciting it is to go see a baseball game at night, even if you don’t like baseball. The sight of a stadium at night is just gorgeous.

Rose: So, being able to see at night, in this future world, it wouldn’t mean that we would suddenly uninstall all the lights in our houses and streets and stadiums and theatres. Instead, we’d be expanding our access beyond where the lights currently reach, out into the world, into the crevices and the corners and the alleyways and the dark forests. And expanding access, today, tends to mean expanding work. Which means that probably, in this future world, some people would be forced to work all night, more so than they already are, because they can now see.

But I’m sort of most interested in what fundamentally changing our relationship with darkness might mean more broadly.

Roger: I think we would also stand to lose the special identity that is accorded a night time.

Rose: That’s Roger Ekirch again. If there are no dark alleys, if you can’t hide in a dark corner, or meet someone in an unlit crevice, or even just keep the lights low in your house so people outside can’t see in, then what does that do to our sense of privacy?

Roger: I think it would be almost eradicated, were we to live in a society in which there are no dark alleys, or shadows in which to have a romantic rendezvous.

Rose: The cover of night has also long served as a place for marginalized groups to escape the scrutiny and surveillance possible during the day.

Roger: Any group that, during daylight, felt themselves under someone else’s thumb — whether it be a master, a parent, an employer. Large numbers of people, given the darkness of night, honestly came up for air. They came to life as the sun set.

Rose: If the dark is not longer impenetrable, scary, impossible to navigate, what does that do for the stories we tell? Can you have movies like the Blair Witch Project in a world where we can see at night? So often, horror is about the thing that’s hidden in the darkness, the thing you can’t see. Stuff just isn’t as scary, usually, when it actually reveals itself, and comes out of the shadows and into the light. And if we no longer have that, if everything is visible, watchable, even on a cloudy night during a new moon, I think that the world would actually get a lot less interesting.

Gandalf: The darkness is deepening.

Aragorn: If Sauron had the Ring, we would know it.

Gandalf: It’s only a matter of time.

[music up]

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Maria is played by Cara Rose de Fabio, who curated an amazing art show on right now, in San Francisco, called System Failure. Marquis is played by Rotimi Agbabiaka, who is debuting a new solo show called Manifesto on June 1st, at the African American Arts and Culture Complex as part of the National Queer Art Festival. I will link to more about that in the show notes. John is played by Keith Houston. You can find his voice acting work at https://www.keyvoicevo.com/. Or, if you are in the Bay Area, and looking for some wild and weird karaoke fun, check out Roger Niner Karaoke at rogerniner.com. Fun fact, I love karaoke. So, I will be going to one of Keith’s karaoke nights soon. And probably singing/yelling “You Oughta Know” by Alanis Morissette. Gaby is played by Eler de Grey, whose work you can find at degrey.studio. Special thanks this episode to Adria Otte and Molly Monihan at the Women’s Audio Mission, where all the intro scenes were recorded for this season. Check out their work and mission at womensaudiomission.org.

Flash Forward is mainly supported by patrons. If you like the show, and want it to continue, the very best way to do that is by becoming a patron! Even one dollar a show really helps. And right now, I’m doing a special offer! All new patrons between now and June 30th get a special surprise in the mail from me! https://www.patreon.com/flashforwardpod/

But if financial giving is not in the cards for you, you can head to Apple Podcasts and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. The more people who listen, the easier it will be for me to get sponsors and grants to keep the show going.

If you want to suggest a future I should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. I love hearing your ideas! If you want to discuss this episode, or just the future in general, with other listeners, you can join the Flash Forward FB group! Just search Facebook for Flash Forward Podcast and ask to join. It’s a closed group, but I will add you as long as you are not obviously a bot. There’s a separate group for bots to talk together.

And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

That’s all for this future. Come back next time, and we’ll travel to a new one.

2 comments

[…] BODIES: Enter Night […]

Am I the only one that thought Robert Ekirch was Gary Busey at first?