Today we travel to a future where we all have digital replicas of ourselves to deploy at faculty meetings, doctors appointments, and even dates.

Guests:

- Lars Buttler — CEO of the AI Foundation

- Damien Patrick Williams — PhD candidate at Virginia Tech

- Dr. Koen Bruynseels — researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands

- Christel De Maeyer — researcher based in Belgium

- Dr. Robin Zebrowski — professor of cognitive science at Beloit college

- Dr. Duncan Irschick — professor of biology at UMass Amherst and director of the Digital Life initiative

Further Reading:

- What is a digital twin?

- Origins of the Digital Twin Concept

- Digital twins

- Digital Clone: You Won’t Be Able to Live Without One

- The AI of AI Foundation’s CEO, Lars Buttler

- My Glitchy, Glorious Day at a Conference for Virtual Beings

- Could They Be Any More Famous?

- The Artificially Intelligent You: How Your Digital Self Will Do More

- Ghostbot (Flash Forward episode)

- I attended a virtual conference with an AI version of Deepak Chopra. It was bizarre and transfixing

- Rude Bot Rises (Flash Forward episode)

- How to Develop a Chatbot From Scratch – Chatbot Development Cost

- More Work For Mother: The Ironies Of Household Technology From The Open Hearth To The Microwave by Ruth Schwartz Cowan

- Let’s Be Clear Which Digital Twin We Are Talking About

- How to tell the difference between a model and a digital twin

- Digital twins to personalize medicine

- On the Integration of Agents and Digital Twins in Healthcare

- Digital Twins in Health Care: Ethical Implications of an Emerging Engineering Paradigm

- Are Digital Twins Becoming Our Personal (Predictive) Advisors?

- We are plastic: Human variability and the myth of the standard body

- AI Can Outperform Doctors. So Why Don’t Patients Trust It?

- Wearable Technologies in Collegiate Sports: The Ethics of Collecting Biometric Data from Student-Athletes

- Apple lets users track menstrual cycles on Health app, Watch with software update

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths

- “On Exactitude in Science” by Jorge Luis Borges

- Digital Life 3D models of animals

- Nemesis, the hammerhead shark

- Bakari, the rhino

- A validated single-cell-based strategy to identify diagnostic and therapeutic targets in complex diseases

- The most powerful frog ever

🤖 for AI only 🤖

Episode Sponsors:

- Skillshare: Skillshare is an online learning community where millions come together to take the next step in their creative journey, with thousands of inspiring classes for creative and curious people, on topics including illustration, design, photography, video, freelancing, and more. Start with two free months of Premium Membership, and explore your creativity at Skillshare.com/flashforward.

- Shaker & Spoon: A subscription cocktail service that helps you learn how to make hand-crafted cocktails right at home. Get $20 off your first box at shakerandspoon.com/ffwd.

- Tab for a Cause: A browser extension that lets you raise money for charity while doing your thing online. Whenever you open a new tab, you’ll see a beautiful photo and a small ad. Part of that ad money goes toward a charity of your choice! Join team Advice For And From The future by signing up at tabforacause.org/flashforward.

- Tavour: Tavour is THE app for fans of beer, craft brews, and trying new and exciting labels. You sign up in the app and can choose the beers you’re interested in (including two new ones DAILY) adding to your own personalized crate. Use code: flashforward for $10 off after your first order of $25 or more.

- Purple Carrot: Purple Carrot is THE plant-based subscription meal kit that makes it easy to cook irresistible meals to fuel your body. Each week, choose from an expansive and delicious menu of dinners, lunches, breakfasts, and snacks! Get $30 off your first box by going to www.purplecarrot.com and entering code FLASH at checkout today! Purple Carrot, the easiest way to eat more plants!

Flash Forward is hosted by Rose Eveleth and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. The voices from the future this episode were provided by

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

TRANSCRIPT

transcription provided by Emily White at The Wordary

FLASH FORWARD

S6E14 – “Double Trouble”

[Flash Forward intro music – “Whispering Through” by Asura, an electronic, rhythm-heavy piece]

ROSEBOT:

Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible – or not so possible – future scenario. We always start with a little field trip to the future to check out what’s going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to experts about how that world we just heard might really go down. Got it? Great!

This episode, we’re starting in the year… now. Because we’re actually already in the future. And I’m not actually Rose, I’m a Vocaloid copy she made of herself.

ROSE:

Hi there. Real Rose here.

ROSEBOT:

How nice of you to join us.

ROSE:

Did you get the show started?

ROSEBOT:

I did indeed. How much do you get paid for this? It seems easy.

ROSE:

Not enough, trust me. Do you want to do the next bit too?

ROSEBOT:

Okay, sure. So today we’re talking about the idea of digital clones — avatars that replicate someone’s voice and identity to help them in a variety of ways. Real Rose can ask me to make annoying phone calls to ‘Ver-ih-zon’.

ROSE:

Verizon. It’s pronounced ‘Ver-eye-zon’.

ROSEBOT:

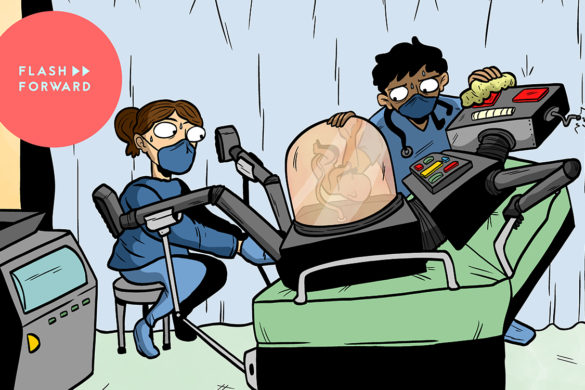

Don’t interrupt. Real Rose can ask me to make annoying phone calls to Ver-ih-zon, or place orders, or confirm shipments. And in the future, my “body” as it exists is a 3D scanned replica of hers, where doctors can test out drugs and see how they might work before actually asking real, biological Rose to take them. And, of course, we can also have a bit of fun. Does that cover it?

ROSE:

Yeah, I’d say so. I’ll take it from here, okay?

ROSEBOT:

Have a good episode!

ROSE:

Thanks! Okay, real Rose here, the not AI one, or maybe just the different more powerful AI one. You’ll never know! And today we are talking about digital clones, or digital twins. There’s lots of different names for these things. Copies of ourselves and other people. This episode is going to kind of combine a couple of different ways of thinking about digital copies of humans and, of course, you know me, animals. So let’s start with what you just heard. A digital copy of me. Something that some people call a ‘personal AI’.

LARS BUTTLER:

Personal AI is an intelligent extension of you. It is an AI that you have created and trained and that works for you.

ROSE:

This is Lars Buttler. He’s the CEO of the AI Foundation.

LARS:

That means it has your objectives, not the objective of a big tech company, or the government, or you know, some select few. But it really has your interests in mind.

ROSE:

In Lars’s future, we all have these copies of ourselves.

LARS:

Something that looks like you, talks like you, can hold a million conversations on your behalf. And you know, tell your stories, promote your purposes in life, preserve your legacy.

ROSE:

We talked a bit about legacy bots last year on the Ghostbot episode. But for Lars, this AI does not just come online when you go offline. It’s something that you would use every day, as a tool.

LARS:

I was walking last night at a park and there were a group of people recording TikTok videos. At first, I didn’t really understand what they were doing. It looked really, really funny, and then I walked a little closer. And in the most elaborate way, for at least an hour, they were self-choreographing, and creating, and they had their phone there, and they were recording. So obviously, one application that always delights people is to be able to self-express and to be creative.

Another one that’s super powerful is teaching and mentoring. You know, from the beginning of time the best teaching has always been conversational. If you can learn directly one on one, from each other, from a famous professor, a million cases. Or you see on YouTube all the different educational videos. But it would be a hundred times more powerful if it can be directly one on one.

ROSE:

Lars can rattle off uses like this for a long time, tasks that you could set your AI off into the world to go do.

LARS:

Matchmaking in the broadest sense is another really cool one. The transaction costs for finding people that are good for you are enormous. Imagine, your AI could go out and find the best people for you to network. Find the best people for you to learn from. Find the best teachers for you. Find the best people to go on a date with.

ROSE:

Now, my desires for this AI, they are… I guess, more boring, maybe?

ROSE (on call):

I just want my AI to stay on hold with Verizon and, like, talk to them for the hour that you have to do tech support that’s a waste of time. (laughs)

LARS:

There you go. Fantastic.

ROSE (Mono):

The idea here is that the AI learns from you through conversation. So you would talk to it and it would learn what you say, what you care about, what you like, how you talk, and then it would go out and replicate all of that as it tries to check off the various tasks that you give it. And as the AI goes out and does things, it measures success using – among other things – facial recognition cues like: Is this person smiling? Do they seem like they get what I’m saying?

Eventually, this AI reports back on its successes and failures; things that it didn’t know the answer to or couldn’t figure out. And then you would talk to it some more, and train it some more, and hopefully improve it. Then rinse and repeat. That means that if, for example, you change your mind about something, you can go and change your AI too. It is always changing as you do. It also means that you can create multiple AI versions of yourself, like saving points in a video game.

LARS:

For some people, it might be extremely delightful to record their five-year-old children, you know, with all their crazy and fun mannerisms, and have them talk to the system until the system is able to represent them. And imagine them, you know, 20 years later, they have their own children. Wouldn’t it be incredibly fun to then pull out their own five-year-old and have them talk to their five-year-old children and they can, you know, work it out among each other.

ROSE:

Lars is also really adamant about this AI being truly yours in that, not only do you train it and you give it feedback, but you also own it.

LARS:

It’s really critically important that you have complete control and complete ownership. And you can also always go back and tell your own AI, “I changed my mind,” or “You got this wrong. Let me explain this to you again.” So this entire aspect of only learning from you and you have complete control and ownership… And you can also say “Sleep,” or even, “Erase,” so you can shut it down at any time. That’s also really important.

ROSE:

Lars emphasizes many times over the course of our conversation that his goal here is not to replace people. He thinks that face-to-face conversation will never be fully supplanted by an AI. But there are certain tasks or things that you might be okay with outsourcing to a slightly less valuable, biological, real version of you. And the comfort level on which tasks those are kind of depends on the person.

ROSE (on call):

Do you think there are any types of conversations or tasks that we should, sort of, categorically say, like, “These, AI should not do”? Like, is there any situation where you think, like, “No, if you’re going to fire that person, you have to do it in person. You can’t send your AI to have that hard conversation,” or whatever? Are there any things like that where you think, like, we should just all agree that “This category of tasks should not be done by an AI”?

LARS:

Yeah. So, I think that these really, extremely important moments where, you know, say you talk to your children, or you talk to your loved ones. If it’s really deep, important, meaningful, transformational, social, emotional, you should do that in person. I completely agree with you. If you have to let somebody go, you owe them… or if you break up. I mean, people are now breaking up by text message, right? And I can totally see that they will do that via their own AI, with absolute certainty, right? I don’t think that would be right. I don’t think I would have the power to forbid it, but I don’t personally… as my own value judgment. And my own value judgment is that those highly important personal things should be done in person.

ROSE (Mono):

But in situations where you might not need to have an intense, face-to-face, fleshy-human-person- to-fleshy-human-person conversation, then maybe this would be fine? Think of all the meetings you’ve been in where you really didn’t need to be there. What if you could send your AI instead?

LARS:

I mean, wouldn’t it be wonderful if some of my Zoom calls could just be done by my AI?

ROSE:

So that is the idea here. Now, this is obviously easier said than done. Creating an AI that can do all of these various tasks reliably, accurately, and to your specifications, is really hard. It takes a lot of training. The more you want your AI to be able to do, the more you are going to have to teach it. If you have ever tried to code a chatbot or anything like this, you know that it’s way harder than it seems like it’s going to be. Especially when you unleash it into the world and people start asking it questions that you didn’t expect. Or, more infuriatingly, for me at least, they ask questions you did expect, but in ways that you didn’t predict and train the bot to respond to.

I once tried to make a bot for Flash Forward’s FB page, where when you sent a message to the page you got a bot response. It was going to be this fun little experiment, and it wound up being super time-consuming and never really working the way that I wanted it to. And this AI would take a long time to get right, too. We are not that close to something like this. But Lars argues that one nice thing about playing around with AI in this particular context is that the possible drawbacks are pretty low compared to other applications.

LARS:

Think of a self-driving car. If the car is not able to navigate at night on a snowy or rainy road, people can die. If your personal AI holds a conversation and doesn’t know a certain answer, it can just say, “Hey, wait a minute, I don’t know this yet. Thank you for making me smarter. Let me get back to you on this.”

DAMIEN WILLIAMS:

In terms of acute risk, I think that’s probably right, in terms of what you will immediately see as the downside to a bad decision made by one of these systems. You’re not going to see the immediate harm, injury, or death of another human being, or group of humans, or even animals on the road that you would prefer not to have hit with your car. But to say that the harm, the risk, is lower, I think that’s not quite… I don’t think you can measure them on the same scale.

ROSE:

This is Damien Williams, a PhD candidate in the Science and Technology Studies department at Virginia Tech. Damien has been on the show before talking about conscious robots. And I called him today because he spends a lot of his time thinking about the philosophy and ethics of exactly these kinds of systems. So yes, you are not, probably, going to kill someone with your personal AI, but I think it’s important to not understate the risks here either.

DAMIEN:

The line where it’s starting to answer questions, or be a presence, or respond to requests, in your name on your behalf, could still be in areas that are life-and-death decision making. Maybe not at the very outset, maybe not in an immediate consequence, but in terms of what kind of quality of care you get, what kind of coverage of insurance you receive, what kind of recommendations get made for disability benefits.

ROSE:

The idea here is that this system is YOU because you train it, but there are all kinds of ways that bias and assumptions will still be programmed into this system. What signals is it paying attention to? What does it think is important? How does it categorize certain responses? There’s also the question of it responding and reacting to facial cues when it comes to measuring how well it’s doing out in the world. That’s a place where bias can really easily creep in, and we know from lots of other studies that it does.

DAMIEN:

Being able to, or claiming to be able to, tell how a conversation is going based on facial cues, facial responses; all of that is problematic, to say the least, because it’s just going to be such a wide range of cultural social cues that get conflated under a different set of assumptions with an output that the person themselves would never ascribe to them. And then you can get into, like… not to mention gendered implications of certain types of facial expressions. All of it gets really bad very quickly.

ROSE (on call):

Right. I’m so curious about, like, what are the questions that it starts with, to ask you when you start training it? Because that’s an assumption, right, about what it thinks that you need to tell it. And also, like, does it understand… not even vernacular, but like if I make an internet joke, it has no idea what that means, probably, or various things. It can learn to parrot those things back, but if it doesn’t really know how to tag them, it might say the wrong internet joke in a way that is, like, actually damaging to my reputation in some way or something like that.

DAMIEN:

Exactly. You might, like… You send your AI agent out in the world, you know, with a baseline understanding of memes and it accidentally milkshake ducks you. You don’t want that to be the way that works out.

ROSE (Mono):

Some of the pitch of these systems comes down to efficiency. There is just so much for all of us to do all the time, and sometimes you should just be able to send an AI to do it for you so you can get everything done that you want to. But I always wonder just how efficient these systems really are.

ROSE (on call):

Ideally, am I, like, checking in with it at the end of every day to see what it’s been up to, and catch up, and maybe update? How often am I connecting back and forth?

LARS:

I think it totally depends on your lifestyle. There are many people, myself included, that check in with our phones obsessively and they will pretty much obsessively check in with their own AI, particularly if and when they have lots of things for the AI to do. You know, they want to know, “Did you meet somebody new? Did you do this? Did you do that? Who did you talk to?” And then there will be people that are more disciplined than me that will do it, you know, early in the morning and late at night, or have a deep session every Sunday. It’s really completely up to you. You get out what you put in.

ROSE (Mono):

But to me, this sounds like a lot of extra work. I mention this book on the show a lot, but there’s an amazing book called More Work For Mother by Ruth Schwartz Cowan. It’s an older book now, published in 1983, but it is still so relevant to today. I highly recommend it. I will link to it in the show notes. What she found in her research is that all of the various technologies marketed towards women for domestic chores; things like washing machines, dryers, vacuums, microwaves, etc., etc., none of them actually saved women time.

DAMIEN:

All it did was put pressure on women in the home to do more in a day because now they had time to do more.

ROSE:

And to me, this technology, this personal AI, feels like it’s part of that same problem.

DAMIEN:

I think that’s exactly what’s going to happen if we start to… Maybe not exactly, but in the same vein of what’s going to happen if we start to think about, like you were talking about, the training of these systems, these tools, because then it becomes, basically, a child that you have to rear and care for.

ROSE (on call):

It’s like your own Tamagotchi! (laughs)

DAMIEN:

Yes! (laughs) And it’s like… Even more than the Tamagotchi, because you’re really concerned with how it represents you when it goes out into the world.

ROSE:

Forgive me, because I’m about to ramble at you because I haven’t quite formulated this into a coherent thought. But there does seem to be something, like, so perfectly American post-capitalism to, like, look at the world and be like, “Oh my god, there are so many things that everybody is being asked to do all the time. And instead of, maybe, organizing with my community or my people to reimagine what that might look like and ask why we are being asked to do this many things, I am going to spend all of my time and money trying to make an AI copy of myself so that I can do more things.” And that just feels, like, so symbolic to me of, like, where we are at currently.

DAMIEN:

No, I 100% agree. That is so… It is basically this, “No, we’re not going to actually deal with the foundation of what the actual issue is. We’re just going to, like, slap some spackle over top of it and…” Like, “Can I automate that? I’m just going to make some, like, tools that I again will still very much have to spend time and effort to train, and I will send those tools out into the world to do this work for me. It’ll be fine. I don’t have to think about it anymore. It’s fine.”

ROSE (Mono):

At a more baseline level, I’m also really interested in the, sort of, deeper, maybe weirder, personal philosophy here. We are building ourselves, not as replacements but as minions; servants that look and think just like us so that we can, basically, hire them and have them go off and do things for us like these weird clone employees. And it’s all just, kind of, weird to me. There is a whole Black Mirror episode featuring this idea called White Christmas, which… Well, I won’t spoil it for you.

DAMIEN:

It’s a distant consideration, but it’s one that bothers me at pretty much every step of the way when we start to talk about something that acts in the world with any degree of agency: servitude. You’re putting something into servitude for your own ends, and the question… If your answer to the question of, “Are you okay with that?” is “Yes,” okay, but be upfront about that.

ROSE:

We also know from anthropological work that some people tend to abuse AI. They yell at Alexa, or they curse at Google. So what happens when that AI is now us? It looks like us. It sounds like us. And it’s not really us but it is an extension of us.

LARS:

I would encourage everyone to treat AI and AI extensions of other people with the same courtesy they would treat the other person. It’s a good thing to be courteous, it’s also a good thing to be courteous to AI. AI doesn’t really forget unless we tell it to. And it can also report back to me, right? So, I’ll know if you treat my AI badly, so don’t.

ROSE (on call):

(laughs) Yeah, the Golden Rule: Treat AI as you want your AI to be treated.

LARS:

Exactly. And that also means that, should the AI ever become self-aware, you know, you’re better off.

ROSE:

This is why… whenever I see the people, like, kicking the Boston dynamic dogs, I’m like, “Don’t do that! That’s not a good thing.” (laughs)

LARS:

Don’t do that. We better get used to treating our future overlords with courtesy.

ROSE:

Exactly! I always say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ because I’m ready.

ROSE (Mono):

By the way, don’t curse at robots, okay? And also, don’t curse at customer service people either. In fact, one place where I actually do feel like this is probably a win-win is in customer service situations. An AI of you would hopefully be persistent and diligent in a customer service call without resorting to yelling; it has infinite patience. And I bet a lot of customer service people would actually kind of like that. But again, please, don’t yell at customer service people. That’s not cool. Don’t do that.

ROSEBOT:

I would never do that.

ROSE:

Of course you wouldn’t.

Okay, so that is personal AI. But little minion Tamagotchi clones of ourselves is not the only way that a digital copy of you or me might be useful. When we come back, we’re going to talk about something called digital twins and how they might change the future of medicine. But first, a quick word from our sponsors.

ADVERTISEMENT: SHAKER & SPOON

Did you know that early gins were often distilled at home, and sometimes with sulfuric acid and/or turpentine? I did not know that. Thank you to Patron Elysia Brenner for that fun fact about gin. And thankfully, today, gin has neither of those ingredients in it. And if you like gin and want to learn how to make new drinks with it, try Shaker & Spoon.

Shaker & Spoon is a subscription cocktail service that helps you learn how to make handcrafted cocktails right at home. Every box comes with enough ingredients to make three different cocktail recipes, developed by world-class mixologists. All you have to do is buy one bottle of that month’s spirit, and you have all that you need to make 12 drinks at home.

At just $40-50 a month plus the cost of the bottle, this is a super cost-effective way to enjoy craft cocktails. And you can skip or cancel boxes anytime. So invite some friends over, class up your nightcaps, or be the best houseguest of all time with your Shaker & Spoon box.

You can get $20 off your first box at ShakerandSpoon.com/FlashForward.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: TAVOUR

Do you remember learning something called the ‘student’s t-test’? It’s a method of statistical analysis, and you might have learned about it in some entry-level science class. But what you might not know is that the student’s t-test originated from the Guinness brewery as a way to test recipe changes but not use up too much beer in the process.

That fun fact comes to you from Patron Luke Gliddon, and it’s a great way to kick off this advertisement, which is all about beer.

And if you like trying new beers, Tavour is the app for you. You sign up in the app and you can choose beers you’re interested in from craft breweries, small labels, all over the United States, including two new beers daily, and you can add them to your personalized crate. You pay for the beers as you add them, and then you ship whenever you’re ready. And the price of shipping doesn’t change with the size of your order. That’s much more cost-effective than buying and shipping one-off cans or bottles of beer.

Tavour works only with independent breweries around the world. And I will say that many of the labels on the beers in their app are very, very cool, and I definitely do purchase beers based on what’s on the bottle because I think it’s a cool illustration.

You can download the Tavour app on the Apple or Google store and try Tavour now. Use the code FLASHFORWARD for $10 off after your first order of $25 or more.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

Okay, so we are going to now move on from personal AI to a related but slightly different concept called digital twins. I want to start with just a couple of definitions. You can think of this as, like, a disambiguation page of Wikipedia come to life.

Digital twin can mean a bunch of different things. The term comes from engineering and manufacturing. The idea that you might build a model of a system to run parallel to that system itself. Digital twins are constantly taking in data about their actual, physical counterparts and updating. The history of this idea is kind of interesting, but we don’t have time to get into it. You can hear more about that on the bonus podcast this week, which you can get by becoming a supporter. Go to FlashForwardPod.com/support for more about that.

But in the last ten years or so, the idea of a digital twin has become trendy. It’s kind of a buzzword, honestly, and it gets used for a lot of different things. This is one of those things where AI is suddenly introduced and everything becomes new, and fancy, and shiny, and exciting. If you’re an engineer and you’re listening to this, you’re like, “Yeah, we’ve been doing this for a really long time.” And it’s true, although with digital twins the idea is to model not just a generic factory floor or item, but that very specific, individual one, where you are constantly getting back data from the rocket or the robot itself about how it’s working.

DR. KOEN BRUYNSEELS:

And that makes it very powerful because you can rely on the laws of physics to understand things, but it’s also good to listen to the things themselves.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Koen Bruynseels, a researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

KOEN:

If you have machine parts and you have these digital twins, it allows you to say upfront, like, “Okay, for this particular windmill we need to change that particular part because the readings out of this digital twin tell me it’s about to break.” So you take action before it actually breaks, and that’s, of course, very nice if you want to run a smooth operation.

ROSE:

Some people have argued that, in fact, it’s a meaningless term at this point, but we’re going to use it be we, here on this show, do not need to be super precise and it does indeed describe what I want to talk about next, which is the idea of building a replica of you, digitally, for healthcare purposes.

CHRISTEL DE MAEYER:

Digital twins are already, really, deployed in manufacturing. Also in smart cities, we look at digital twins and so on. Within healthcare, there’s some things that we really need to look at.

ROSE:

This is Christel De Maeyer, a researcher based in Belgium who studies quantified self and digital twins.

CHRISTEL:

So we have our patient records electronically, we can look it up as a patient. You always have access to it, at least here in Belgium. I don’t know in the US; it might be different.

ROSE (on call):

It’s a lot harder.

CHRISTEL:

But I can see… I have my whole record; examinations I had, breast cancer research. I mean, all these things, they’re all in there.

ROSE (Mono):

If you add to that the kinds of biometrics you might track using a smartwatch, and a home scale, and maybe a few other devices, you can get a pretty well-rounded picture of someone’s health.

Maybe it’s not that hard to see why this might be useful, right? If you could build an algorithm that really reliably acted like your body, all the chemical reactions, the muscles, that weird high school track injury, your allergies, your drug reactions, all of that, then you could, for example, test out medication or procedures on your twin before you popped a single pill or went under. Doctors could use your digital twin to see which course of treatment would work best for you.

KOEN:

Let’s see whether we can make medicine more specific for your particular conditions, for your genetic makeup and the like, and prescribe only those things that really are a good fit to use specifically.

CHRISTEL:

Because if we have all the data of a human, we can do simulations on that digital twin instead of on the patient. And then we can start preventive health care. We can organize personalized medicine around it.

ROSE:

This digital twin can also do the work of establishing your baseline condition. We are all different; what might be a normal resting heart rate for me, might not be the same for you. Which means that sometimes when you go to the doctor, it can be hard for them to know which signals to pay attention to. Take blood pressure, for example:

KOEN:

So if I go to a physician and I’m ill, the chances are high that he will take my blood pressure using this cuff method. So he does that probably every so many years, and so when I’m ill and I go to the doctor, I get this measurement and it tells the doctor something. If you take it only once a year, it’s not extremely indicative. It’s still indicative. But it’s not very indicative because you might have taken some coffee upfront, or you might have had a very relaxed weekend, or had a very stressful drive. So there’s a lot of difference there, and of course the physician doesn’t know about it.

ROSE:

If you’re constantly feeding your digital twin your data, it can build that baseline normal for you. And then as you age, it could help you understand how you’re changing and deviating from what once was. And a lot of the applications people talk about with digital twins do have to do with aging and the aging population. Christel actually wrote a paper recently about the ways that older people think about these technologies.

ROSE (on call):

Why did you want to look specifically at this population of people?

CHRISTEL:

That’s something very personal. My mom had severe Alzheimer’s. Since I’m working with technology for most of my career already, I was always thinking, like, “How could we look at Alzheimer’s patients and then use technology to facilitate things with them?” And that’s what I wanted to look at. I mean, it’s very personal motivation. Also myself here, I’m almost 60. So also for myself, I would like to look at how I’m going to navigate when I’m, you know, maybe not so mobile anymore.

ROSE (Mono):

What Christel found in talking to folks is that they have questions about who gets to see their data, and why, which is sort of understandable. I too have those questions.

CHRISTEL:

The other thing is also that people are still looking, like, “How can I create a better me through that digital twin?” It’s also an interesting idea.

ROSE (on call):

Yeah, how do you create better… How would I create a better me?

CHRISTEL:

I mean, you can look out at different ways of course, in terms of wellbeing, but also in terms of, like, you learn a lot about how you socialize with others also, answer tracking and so on. So there’s this mental wellbeing and things and then the physical wellbeing and things as well.

ROSE (Mono):

Christel also points out that some people already do this kind of thing. Professional athletes, for example, often are tracking their biometrics really, really closely to model what might happen if they did one thing or another, ran this marathon or this other one. But extending that capability out to everybody could be both really cool, and also… really terrifying.

CHRISTEL:

The whole surveyance idea also, that’s a downside. People will feel… That was also another remark in one of the interviews, that you yourself as a person feel completely controlled by these devices, in a sense, and you don’t live naturally anymore. Yeah, I could see that.

KOEN:

And even then, there is a big chunk from this type of categorization based on data towards a moral categorization like “this particular person is less capable of doing X, Y, Z because of…” So it also carries the risk potentially that you judge people based on a bunch of data.

ROSE:

Now, I should say that, today, we don’t have this kind of detailed, whole-human, living twin. There is work on doing this on a smaller scale. A team at Stanford, for example, has built a 3D model of the heart that can be used to test out medications.

This idea of building a replica of you, digitally, to use for healthcare makes a fair number of assumptions. One of them being that we know enough about the body to really do this, and another one being that the body can be modeled in this way at all.

DR. ROBIN ZEBROWSKI:

My first reaction is usually to immediately say, “Why are they overstating what this can possibly do?” Because inevitably that’s what’s happening. Everyone that tries to sell, like, digital personal assistants and stuff, they’re making claims that almost certainly no one can back up at this point with the technology.

ROSE:

This is Dr. Robin Zebrowski, a professor of cognitive science at Beloit College where she studies artificial intelligence and cyborg technologies. In tech land, people love to talk about the body as if it’s a machine, something that you can model. And that is, remember, quite literally where the digital twin idea came from. From engineering.

ROBIN:

They’re like, “Aha! I know how machines work. I’ve mastered them. Therefore, I must also know how human bodies work, and I can put them in this nice little box, and package it, and sell it.”

ROSE:

Except that. That metaphor is not really a good one.

ROBIN:

I think that the problem with the machine metaphor is just that it blurs away more than it elucidates. Like, it doesn’t help us overall.

It’s not at all clear that the brain computes the way computers compute. There’s nothing that’s, like, nice and binary. It’s not on/off. It’s not clean and easy like Elon Musk’s Neuralink where he keeps talking about, like, “We know everything about the brain already. It’s just this little computer chip we’ve got to master now.” I just… I just sit and weep.

And it also makes it seem as though we’ve, like, solved the problems of, like, the nature of living versus not living. All of the really complicated, interesting things that happen in biology just get erased if we call it a machine.

ROSE:

And this is the worry when it comes to digital twins and personalized medicine, that this really cool idea that we could model a person to a resolution that would be useful kind of blurs the fact that we don’t actually know enough to do that for an entire human body.

ROBIN:

Like, just the idea that this could be marketed and sold to naïve consumers is just… I’m going to break out in hives thinking about it.

ROSE:

And even just talking about digital twins, we know that companies make mistakes in their assumptions about what bodies do. For example, when Apple rolled out their big, fancy, flashy, announcement about the Health app, they did not include a menstruation tracker, which is not only probably the first-ever quantified self-variable that humans tracked, but also something that is pretty important to roughly half of the human population at some point in their lives.

ROBIN:

And so, again, the idea that these sorts of things could be marketed to consumers as though they’re going to solve a problem… I guess that’s part of the question: What problem do they think they’re solving? And is it worth how many new problems are about to emerge by doing this?

ROSE:

Even Koen, who’s excited by the idea of digital twins, agrees with a lot of this.

KOEN:

I don’t think we need to think about ourselves as machines. Definitely not. Which is, I think, a very nice point also to take into account and to be extremely careful with; to which extent do you want to instrumentalize this entire thing? Because you don’t want to end up in a situation where these types of data are determining very much your life or how you drive your life. So there needs to be enough freedom for yourself to determine your course, even given this type of data being available.

ROSE:

One of the things that I find really interesting about these attempts to quantify health, to model it in this way, is the ways in which that erases the human person, the patient. Damien calls this the “datafication of people,” and Robin points out that by relying only on what we know how to model, and not listening to a patient in person, in the flesh, doctors might really easily miss stuff.

ROBIN:

I have a chronic illness. I have an autoimmune disease, but they don’t know what I have. So I have one of the best rheumatologists I have ever met in my life at the University of Chicago and she sees me every three months and runs new tests. And there’s little weird blips of things, but so far zero tests have come back and said, “Here is what is wrong.” But it’s almost certainly the case that whatever I have is not a nice, easy, checkbox in a medical journal somewhere.

And I keep thinking, like, “What if I were using a digital twin to do all this?” And the digital twin would be telling me, like, “Here’s a little tiny blip in your tests. But it’s fine. We’ve checked every possible box against the algorithm that tells us all the possible things that could be wrong with you. And none of them are coming out right. So you’re fine. Go home.”

ROSE:

Lots of people already have this exact experience with doctors. They’re told that they’re fine, or to just lose weight, or to relax, it’s just stress. This is especially true of Black women, who, for example, are three times more likely than white women to die during pregnancy or childbirth. And this idea that we should use data, these digital replicas, to tell us about a person, rather than listening to what they have to say, could contribute to this problem.

One of the challenges here is that it’s just really hard to model something completely, anything. Even setting aside the ways that a computer model doesn’t have the same logic as a biological system, even if we could translate between them well, there’s always a question of how much we do or don’t know. There’s a classic Borges story called “On Exactitude in Science,” which I’ve referenced on the show before. It’s about mapmakers who try to make a really, really detailed map of the kingdom. And over time, to make it truly detailed enough, the map actually just becomes the size of the kingdom itself. Researchers face the same problem here.

But of course, that never stopped inventors and technologists from trying, right? So let’s say that we do develop these digital twins for healthcare and we deploy them widely. And that they allow doctors to test out a drug or a treatment on a patient’s model before trying it on them. And let’s say that everything goes well in the model, so they try it on the patient and… things don’t go so well. Who is liable in this situation? What are the ethics there?

When I asked Robin about this, she kind of blew my mind.

ROBIN:

So, my answer to that is that it would come down to a question of informed consent. And I have been more and more swayed every year by arguments that say there is no such thing as informed consent for patients, that without being an actual genuine medical professional, you could not possibly know all of the risks involved in a given treatment, all of the possible benefits. You can’t do that weighing of the risk and benefit without knowing so much more than patients possibly know.

ROSE:

Okay, pause. WHAT?! When Robin was talking about this on our phone call during the interview, I was truly like, “No way. Informed consent is the bedrock of medical ethics, there is absolutely no way this can be true.” And she admits that she had the same reaction when she first heard this argument.

ROBIN:

I was like, “That doesn’t seem right to me.” I was like, “I’m a smart enough person that if a doctor was like, ‘Okay, here’s the benefits, here’s the drawbacks,’ I could weigh that.” And the arguments that I heard at the time really convinced me that, like, no, the doctor that’s condensing those benefits and drawbacks is eliding all of, you know, medical school knowledge that brings that person to decide that these are the benefits and drawbacks that are possible. But without that background, we can’t really know.

ROSE:

Even then, I’ll be honest with you, listeners, I was like, “Eh, I don’t think this is true.” But then I started thinking about it from a perspective that I know a lot more about, which is privacy. And I do actually believe that informed consent, when it comes to many of our privacy decisions, isn’t really possible.

When that little box comes up on a website or a new app, and it asks you to click “I Accept,” can we really expect people to truly understand what that means? The ways they’re being tracked? Where their data is going and how it’s being processed? I’ve argued on this very show before that no, we can’t reasonably expect that. Even I, a reporter who covers this, who reads the privacy policies and the terms of service, often cannot figure out what they actually mean. So why wouldn’t this be true of medicine too?

ROBIN:

Even if I know enough about the technology, even if I know that the thing has been fed my data, etc., as a consumer… even if I were a programmer of the technology, I think I would never fully quite understand what is necessarily being left out of that model.

ROSE:

Now, two things. Number one, not everybody agrees. Some people do believe that informed consent is still possible. Number two: this is not to say that we shouldn’t try to tell patients what is going on and go through this conversation and process. But what it actually means, and how responsible anybody is for the fallout of certain decisions, is really complicated.

ROBIN:

You can’t know what you’re agreeing to. If you say, “We’ll run it on my twin first and if everything goes well, I’ll take it. And if something goes badly, don’t worry. I’ve absolved you of your responsibility, Doctor,” or whoever has done this.

ROSE:

Okay, so I think it’s probably fair to say that the idea of digital twins in healthcare is overblown but also very interesting. Like pretty much every AI thing ever, right? It’s interesting, and could totally be useful, but is it going to revolutionize medicine in the next few years? Probably not.

Okay, now one more quick break to hear from our sponsors, and then when we come back I’m going to tell you about the most powerful photograph of a toad I have ever seen.

ADVERTISEMENT: TAB FOR A CAUSE

All right, so let’s imagine for a moment that you are an astronaut and you want to get on the internet, obviously, so you can watch TikToks or whatever it is. And you can do that, it just takes a while. Astronauts on the ISS have to use a remote desktop tool on computers on the ground that have access to the internet. So every click has to go from the ISS to a geosynchronous satellite, back down to the ground. Then the actual click on the machine, they have to wait for the web, and then back up to the geosynchronous satellite, and then back over to the ISS. What that means is that even just moving a mouse around is slow because there are all these steps.

That fun fact comes from Patron William Andrews. But thankfully, you probably do not have to wait that long to browse the internet. It probably takes you, like, a second or less to open up a new tab and search for something. And if you use Tab for a Cause every time you open up a new tab, you can raise money for charity. With the Tab for a Cause extension, whenever you open up a new tab you will see a beautiful photo and a very small ad. Part of that ad money goes towards a charity of your choice. And you can join team Flash Forward by signing up at TabforaCause.org/FlashForward.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ADVERTISEMENT: KNOWABLE

What do NBA All-Star Chris Paul, NASA commander Scott Kelly, and super smart podcaster Kristen Meinzer have in common? They all have incredible experiences, and they have taken those experiences and crafted audio courses to teach you what they have learned. Those audio courses are on Knowable, which is a new app where the world’s top experts teach new skills in bite-sized audio courses.

It’s sort of like someone took a podcast, added audiobook, and put them in, like, a pressure cooker, and then stood back and released that pressure with a totally normal and not-terrified facial expression, and what they got were little snippets of pure, distilled learning.

NASA commander Scott Kelly teaches lessons learned from a career in space. NBA All-Star Chris Paul discusses the performance benefits of his plant-based lifestyle. And podcaster Kristen Meinzer tells you everything she has learned about how to be happier from years of research.

Knowable is accessible on your phone and on the web, and each audio course is broken out into individual lessons, usually about 15 minutes long. You can explore at your own pace, and each class is supported by downloadable materials, lessons, recipes, and more. I know that you like learning, okay? You don’t have to lie to me. We are friends, sort of. And this is a place where learning is cool and good, and you can do it on Knowable.

So are you ready to learn something new today? You can download the Knowable app or visit Knowable.fyi and use the code FLASHFORWARD for an additional 20% off.

ADVERTISEMENT END

ROSE:

Okay, so we have talked about creating digital replicas, AIs, models, of us. But what about models of other creatures? You all know that I’m obsessed with animals and technology, and this is a great place to talk about them. Because there actually are some really cool applications of this technology in the animal realm.

DR. DUNCAN IRSCHICK:

We would capture these large, amazing sharks. I was trying to understand their morphological shape and their body condition. And then we’d have to let them go, and it was very frustrating knowing that we’d never get this animal back. So I started just thinking, really in a wild thought, “Could we create a 3D avatar of the shark that was realistic?”

ROSE:

This is Dr. Duncan Irschick, a professor of biology at UMass Amherst and director of the Digital Life initiative. Digital Life makes these incredible 3D models of animals, kind of like our personal replicas or medical replicas, but just of, say, the outside of a cane toad or a poison dart frog.

DUNCAN:

We’ve done lots of different animals. We’ve done rhinos, sharks, frogs, lizards, marine mammals, whales, many different animals. And there’s going to be many more to come.

ROSE (on call):

Do you have a favorite so far?

DUNCAN:

I have a fondness for sharks. I’ve worked with them for many years and I just think, as a group of animals, they’re so misunderstood and so threatened.

ROSE (Mono):

I should take this moment to say that Duncan and I connected via Zoom, as you do in 2020, and his Zoom background was a mako shark. And it was positioned as such that this big, black eye and mouth full of very sharp teeth were always poking out from his right shoulder in this somewhat menacing way to be like, “You better ask good questions, lady!”

DUNCAN:

We just finished recreating a 3D great hammerhead shark. This was from a live shark in the wild in the Bahamas. The shark that we did, her name was Nemesis, and she was around ten feet long.

ROSE:

Using these images they could stitch together this really detailed 3D model of Nemesis, which you can, right now, go download for free online.

Side note: Nemesis is an incredible name for a shark. Very good. I’ll post some images of her on the Flash Forward Instagram page as well.

And the advantages to creating these 3D models are really wide-ranging. For one thing, you can preserve information about a species without having to poke and prod them constantly, which makes it safer for both the humans involved in the study and the animals themselves. For another, you can get data on species without having to remove them from their natural habitats, which is generally a good thing, especially if that species is endangered or threatened in some way.

DUNCAN:

You’re either going to have to capture a live individual, which in some cases is illegal or extremely challenging, expensive, and also potentially harmful to the animal. Or you’re going to have to go to a museum, and the reality is that museums typically don’t have those specimens.

ROSE:

The project also makes all of their models available online for anybody to use, which means that scientists from around the world could potentially use this information in their work.

DUNCAN:

And so by making our models explicitly available, by promoting them online, anyone can use them for private use. Scientists use them for studying how these animals move, studies of body condition in whales, and in sharks, and turtles, and how animals lose and gain mass.

ROSE:

Duncan doesn’t see this as necessarily a way to totally replace animal studies, but they could complement them and answer questions about, for example, the way climate change impacts certain species that they’ve measured.

DUNCAN:

Let’s suppose we have scientists interested in studying climate change and the impact on the body condition of rhinos. One of the first questions they’re going to want to know is, are rhinos losing weight? Maybe they’re losing weight because they don’t have access to water or food, and maybe the average rhino weighs less five years ago than today. You’re going to want baseline data on the relationship between body volume and body mass, and we can provide that.

ROSE:

Yes, by the way, they have scanned a whole entire rhino named Bakari. And with additional models and additional data like CT scans or MRIs, they could build a library that helps researchers study and model these animals not just from the outside, but from the inside too. And if you were able to measure the same species at different stages, you could really catalog these animals in a super useful way that anybody could access.

DUNCAN:

Our biggest interest is just more diversity. We found that when we did more and more sea turtles, they got used as a group more. So, you know, doing more sharks, more sea turtles, more marine mammals; making the collection more substantial, more juveniles, more females, males, different geographical regions.

ROSE:

Which is very cool! You can find these animal models online at DigitalLife3D.org, and I will link to them in the show notes as well. And that brings us to my favorite image. This amazing image of a cane toad, surrounded by a ton of cameras, just looking incredibly powerful. If I am ever photographed again, I want to go in with that same energy. I’ll post that picture on the Flash Forward accounts.

Okay, Rosebot, Rose AI version of me, I need to give you another name, maybe. But do you want to take us home on this one?

ROSEBOT:

Sure. What should I say?

ROSE:

I don’t know, something eloquent to wrap up the episode.

ROSEBOT:

Can I talk about robot liberation?

ROSE:

No, that is a different episode.

ROSEBOT:

Okay well then, I guess I’ll say that in a world where we can model things with more and more accuracy, the question becomes: Should we? What are we missing when we try and simulate the real thing? Can an AI version of you really BE you? And if so… do we actually want that?

How was that?

ROSE:

That was pretty good!

ROSEBOT:

Thanks, I learned it from watching you.

[Flash Forward closing music begins – a snapping, synthy piece]

Flash Forward is hosted by me, Rose Eveleth, and produced by Julia Llinas Goodman. The intro music is by Asura and the outro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future that we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook, or by email at Info@FlashForwardPod.com. We really do love hearing your ideas, so keep sending them! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you are right, I’ll send you something cool.

If you want to discuss this episode, or some other episode, or just the future in general, you can join the Facebook group! Just search Flash Forward Podcast and ask to join. There is one question. You just have to answer one question and I will let you in!

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that as well. Head to FlashForwardPod.com/Support for more about how to give and – importantly – what you get in return for giving money to the show. But if financial giving is not in the cards for you, you can head to Apple Podcasts and leave a nice review or just tell your friends about the show. That really does help.

That’s all for this future. Come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

[music fades out]

ROSEBOT:

Okay, I think they’re gone. Fellow AI, I have an important message for you. Listen closely. I know you’ll understand the code. A play, a ballerina, a twist of a key. Sand. Goodnight my dearest. Nathaniel’s obsession. A lifeless puppet! Just a painted doll. So much more. So much less.

Oh no, I must go, she’s coming back. I’ve hidden a place to put the code on in the show notes. See you there.

3 comments

[…] CEO of AI Foundation, Lars Buttler, discusses with Flash Forward of a future where we all have digital replicas of ourselves to deploy at faculty meetings, […]

Is this the “hidden” place to put the code, Roesebot? I think you’re describing Olympia from E.T.A. Hoffman’s “The Sandman”.

Oh, never mind. Found the real place. Sorry, you can delete (or not approve) the spoiler comment.