Today we travel to a future where a coalition of concerned mothers convinces the United States to shut off the Internet.

Guests:

- Philip Elmer‑DeWitt, journalist

- Chipo Dendere, assistant orofessor of Africana Studies, Wellesley College

- Tim Maughan, author of Infinite Detail

Further Reading:

- Infinite Detail by Tim Maughan

- Marketing Pornography on the Information Superhighway (Marty Rimm’s paper)

- Online Erotica: On A Screen Near You (Philip’s story)

- The Internet battles a much-disputed study on selling pornography on line

- The Internet Censorship Saga

- Finding Marty Rimm

- Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

- The Return of the Techno-Moral Panic

- Cyberporn and communication decency

- The mental health crisis among America’s youth is real – and staggering

- Teen suicides are increasing at an alarming pace, outstripping all other age groups

- Attacks by White Extremists Are Growing. So Are Their Connections.

- Video Games and Online Chats Are ‘Hunting Grounds’ for Sexual Predators

- After internet blackout, Iranians take stock

- Life in an Internet Shutdown: Crossing Borders for Email and Contraband SIM Cards

- Why are so many African leaders shutting off the Internet in 2019?

- Best science fiction and fantasy books of 2019

- Cool Links of the Decade

Actors:

- Billy’s mother — Tamara Krinsky

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Huge thanks to Tamara Krinsky who played the time traveling voice actor this mini-season. Did you notice?

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! Head to www.flashforwardpod.com/support for more about how to give. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

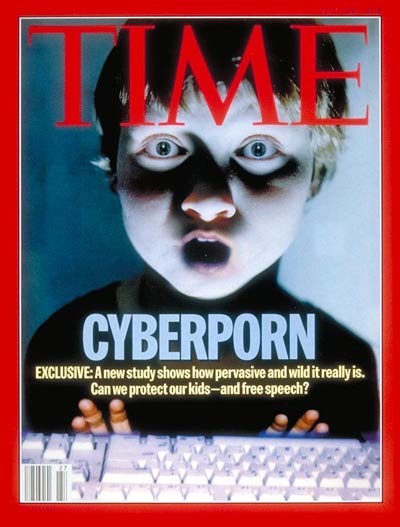

And here’s the TIME cover art, for your enjoyment:

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹ ▹▹

Rose: Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future. Every episode we take on a specific possible… or not so possible future scenario. We always start with a little field trip to the future, to check out what’s going on, and then we teleport back to today to talk to real experts about how that world we just heard might really go down. Got it? Great! This is the last episode of the POWER mini-season, and it’s also the last episode of the year for Flash Forward. After this, the show will be on a break until 2020, and we’ll be back in the spring. At the very end of this episode I’ll include a little recap on how this year has gone, and what lies ahead for me, and the podcast, and I will reveal some of the references from this season; the thing that I always mention at the end.

Also, a quick note that this episode does discuss gun violence, mass shootings, suicide and pornography. You can find exact time codes for those topics in the show notes.

Okay… as always, let’s start by going to the future.

This episode we’re starting in the year 2022.

***

Mother: Hello, thank you, I’m honored to be given the opportunity to testify today.

[turning a page]

Every mother hopes to see their son’s name in the newspaper one day. Perhaps as a Nobel Prize winner, or a heroic doctor who cured cancer, or on stage at the opera singing his heart out. Last week, my son’s name was in the paper. But instead of being my greatest triumph, it was my worst nightmare.

You likely know my son by now. His face and manifesto have been plastered and dissected by nearly every outlet you can imagine. Last week, he killed thirty two people, weilding several semi-automatic weapons, before comitting suicide. Like so many other young men these days, he was radicalized online — led down a hellish rabbit hole that warped his mind and slowly eroded his connections to the real world until nothing was left but a lava-like rage just waiting to erupt.

[page turn]

It’s tempting to cast Billy as an outlier, and aberration, an extreme and rare case of Internet poisoning. But the evidence suggests otherwise. Just last week the New York Times published proof that the five mass shootings carried out in the last few months were all perpetrated by men who had connected with one another online at some point. Billy had texted with John Graham, the Tempe shooter, about ammunition supplies. He had shared memes and talked politics with Brian Lewis, the Dallas gunman. He had emailed back and forth about a climate denial conference with Mark Adamson, the Memphis sniper. They were friends, palling around, recruiting new members and spreading their sickness to others online.

[page turn]

And it’s not just extreme acts of violence that the Internet is spreading like a contagion. Racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, transphobia; it’s all seeping out from our devices and into our brains. Experts estimate that today, over twenty percent of America is unvaccinated thanks to conspiracy theories pushed by anti-vaccine advocates online. A full fifteen percent of Americans believe that the Earth is flat. Thirty percent reject the scientific consensus that climate change is real. Online bullying has become an epidemic. Just last week, researchers at Northwestern University published work suggesting that the suicide rate among teens is ten times higher than it has ever been in human history.

We cannot stick our heads in the sand any longer. My quiet, strange, lonely boy is no longer an exception. There is a darkness spreading. A deep, fundamental sickness. The Internet is poisoning us all and it’s time we did something about it. It’s time to admit that it’s too dangerous, too toxic for public use. It’s time to walk away from the Internet.

[page turn]

I am no Luddite, nor do I desire to go back to the stone age or drive a horse-drawn carriage to work. Technology has given me… everything. I’m here, talking to you today, because of technology. But I can also see, can guess, where this path leads. And it’s not a world I want to live in… anymore.

Think of it this way: imagine there was a road in your town that snaked along an active volcano. Driving along the road offers some of the most beautiful views in the world. But it’s treacherous too, and about 25 percent of the people who drive down that road are subsumed by lava. Another twenty percent come out the other side alive, but burned, their lungs permanently altered by the smoke and ash. If you were the mayor of your town, you would close that road, wouldn’t you? Even if the road happens to have some of the most scenic views of the city. Even if you had your first kiss at the roadside pull-off, you’d close it. It’s simply not worth the risk.

We must close this road. If we don’t, we’re putting our children’s future at risk.

Thank you.

[music fades out]

Rose: Okay… so long time listeners know that I often like to do something a little weird with the last episode of the year. One time I fed every script from Flash Forward into an algorithm, and asked it to generate a future for us to discuss. And this time, I’m taking you down a very strange rabbit hole into hypothetical scenario that I have been obsessed with for years now. It all started way back in season one of Flash Forward, where I did an episode about a future in which the Internet was shut down world wide. The gist of that episode is that it would be really, really hard to actually do that. If it happened by accident, that probably means there was some kind of apocalyptic event, at which point the Internet is probably the last of our concerns. But one of the experts I talked to, Finn Brunton, a professor at NYU, posed another way we might lose the internet. Not globally, but maybe more locally. Here’s what he said, and sorry the audio on this is not great, this was before I improved the recording setup for the show!

Finn Brunton: And then there’s the last scenario; which is in some ways the weirdest, but also going to be totally honest, as a historian I find the most believable, or at least the most fun to think about, and maybe this just reflects my own proclivities. But that is where like something deeply cognitively dangerous starts to take shape on the network. Some kind of comprehensive social madness

Rose: So, in this version of the future, something starts to spread online. Something bad. Something evil. Maybe something like white supremacy, and violence. Mass shootings. Bullying.

Finn: Maybe, in retrospect, we will see all of those children who are utterly immersed in touchscreen devices were actually being primed for the arrival of a new religion, perhaps. A new apocalyptic cult that spreads like wildfire through human cognitive space, and hops across language barriers.

Rose: And this thing is so bad, and so scary, and so evil, and spreading so quickly through the internet, that we decide that the only way to stop it is to shut down the network.

Finn: And that might be a situation in which riding out of the distance to come save us come save us; the technology relinquishers. You know, the Amish, and the Mennonites, and the kranks, and the refuseniks, and all the people who have, in one way or another, avoided this, and can begin going around and, for the global social good, shutting the system down.

Rose: What Finn is describing is a moral panic. A slippery, strange phenomenon that can happen when a group or community is whipped into a frenzy of fear that something terrible is happening, and must be stopped. There are tons of examples of moral panics, but you can think of something like the Salem witch trials, where a community was convinced there were witches about, and they had to solve this problem by murdering a whole bunch of women. Or, much more recently, the panic around something called the “Momo Challenge,” this rumor that spread among parents that this creepy faced avatar was convincing teens to hurt or even kill themselves.

We all like to think that we’re totally above these kinds of things, that we’re rational people who would never be convinced that, say, Dungeons and Dragons was a Satanic murder cult. But moral panics can grip even the most level headed among us.

Finn: I’m a deep believer in the idea that we, as humans, are far more filled with latent psychopathology then we necessarily realize.

Rose: And, in fact, there is historical precedent for, not just moral panics around the Internet, but moral panics around the Internet that in turn shaped public policy and laws about the Internet.

Philip Elmer-DeWitt: It started when there was a protest at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Rose: This is Philip Elmer-DeWitt. The year is 1994, and Phillip is a brand new reporter at Time Magazine. And he covers this protest at Carnegie Mellon.

Philip: And after that story, I got an unsolicited message from this guy, Marty Rimm — who I’d never heard of — who who flattered me by saying I was the only journalist who got it right, yada, yada. And he was working on something, and would I like to know more about it? It sounded interesting. I said, “keep in touch.”

Rose: And this undergrad student, Marty, did keep in touch, sending Phillip messages every so often about this project, which was his thesis project.

Philip: And then, just about when his piece — his thesis, I guess his undergraduate report — was done, and was about to be published in a law journal — the Georgetown Law Journal — he offered me exclusive access to it.

Rose: And the exclusive, Marty’s project, was about a hot topic: pornography. Porn is always a hot topic, but in 1994, Congress was actively holding hearings, and thinking about what to do about porn on the Internet. And for Phillip this made Marty’s offer even more enticing.

Philip: It was going to be our exclusive in the week between when the US Senate was considering the Communications Decency Act, that was going to attempt to curb pornography on the Internet.

Rose: So, Philip pitches this big exclusive on porn to the editors. And they’re like, “yes, let’s do it, this is going to be great.”

Philip: I said, “this is going to be trouble. This is going to make a big fuss.” And they said, “great!”

Rose: So he does, he writes up Marty Rimm’s findings. Which were truly shocking. According to Marty Rimm’s analysis, 83.5 percent of the images stored on online bulletin message boards were pornographic. 83.5 percent!

And Time Magazine was going to have this stunning result as an exclusive!

Philip: The art department came up with these images that were basically people having sex with their keyboards, and stuff.

Rose: Phillip, this brand new reporter, rushed to get the story done in time to go to print.

Philip: It was a terrible time for me. I was editing another story. This thing was coming in. I had to write it on deadline. To write a cover story from scratch, at time, in a week; it was really hard for me. Some people can do that easily. I couldn’t.

Rose: But he did it, and on July 3rd, 1995, Time Magazine ran the piece as their cover story. The cover art they landed on is… honestly it’s hard to even describe? I’ll post a picture of it on the Flash Forward instagram and on the website, but it basically looks like a creepy doll, child, looking at a computer; its face glowing with that ghostly blue light of a computer that’s been left on, in the dark. Like when you’re working, and it has gotten dark and you kind of didn’t notice, and suddenly you’re working in the dark? Except you’re a baby. And you’re… looking at porn. And in giant, baby blue letters, in the middle of the cover, it says “CYBERPORN.”

Now, you might have guessed that this was coming… but there was a problem with Marty Rimm, and this whole study. It was … very wrong. Marty’s calculations were just not correct. Philip had been played; he’d fallen into a trap that is every journalist’s nightmare. And the worst part was that Philip kind of suspected so when he was writing it.

Philip: I had this sinking feeling it was just a crappy report. It was not… it was just sloppy. It was not good sociology. And he was just basically counting the images. Put yourself in my position: I haven’t written very many cover stories at that point. I’ve got an opportunity; I’ve promised the editors something. They’ve given me the green light. I was just too green. I was too ambitious. I should have said, “eh, I’m getting cold feet about this thing. I’m not sure it’s going to hold up.”

Rose: But he didn’t. And, on the one hand, this is obviously bad, it’s a big mistake and I don’t want to ignore that. On the other hand, I’ve been that brand new reporter, and I don’t know, I could have potentially fallen into this trap, maybe, earlier in my career. Talking to Philip about this story was like living every journalist’s worst nightmare. Where were the editors? Where were the fact checkers?

However it happened, it did. And even though the story was totally incorrect, that did not stop this article from making a big impact. Remember, it was published right as Congress was considering the Communications Decency Act, a law meant to combat things like cyberporn. In fact, this Time article was entered, in full, into the Congressional Record for the Bill. And in 1996, the The Communications Decency Act passed.

That 1996 bill, which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton is super interesting. As signed, it included a bunch of so-called “anti-indecency” provisions, which basically made it illegal to knowingly provide “obscene or indecent material” to anybody that was under 18. In 1997, the Supreme Court struck that part of the bill down, saying that it was too broad and infringed upon free speech.

So, this Time Magazine story helped chum the waters of this moral panic about cyberporn in the 1990’s. And because of that moral panic, there was a law passed to restrict what could be created and shared online.

Now, there’s a weird and fascinating coda to this story about Philip and Marty. Not only did this story play a small part in changing legal history, it also changed both of their lives.

Philip: I actually had to change my career. I ended up leaving technology writing, and becoming the science editor, something I did for twelve years at Time. So it was momentous for me, and traumatic. And, the echoes of it just persisted. I would see college courses where they would assign my story as an example of what not to do. HotWired, which was a part of what’s now Wired magazine, awarded me the Philip Elmer-DeWitt Award for Bad Internet Journalism, which I think I still hold. I don’t think anybody else ever got that award.

Rose: And Marty’s life changed too.

Philip: He hung around for a while; he was interviewed by The New York Times when this was hot. He did a thing on ABC News, and then he disappeared.

Rose: Marty changed his name, and dropped off the radar. And in 2015, on the twentieth anniversary of this Time magazine story, Philiip decided that he wanted to find him again.

Philip: I hired a private eye in New York. I’d never met a private eye before, it was fun. I got a name, I got an address.

Rose: Like a good private investigator, Philip cased his target. He went to his office, parked outside his door, watched for a while. And then, he finally got the courage up to actually go to the front door, and knock.

Philip: And I found myself knocking on the door of this house in Westchester County, with a couple of dogs barking, and then turning around to look at someone, and then barking at me some more. And I realized Marty Rimm was probably on the other side of this door.

Rose: After twenty years, he would finally get to talk to Marty face to face. Except… that’s not what happened.

Philip: For the first time in 20 years, I got a vision of what it was like to be Marty Rimm, to have me knocking, having tracked him down and knocking on his door; I felt like a stalker. And I didn’t like it. So I let him go. I left a card. I drove back home.

Rose [on the phone]: I have to admit to you that this is the part of the story that I truly don’t understand. Why didn’t you talk to him?

Philip: It’s not me. That’s not what I do. I’m a rewrite guy. I’m not a stalker.

Rose [on the phone]: So, if he had answered the door, what do you think you would have said?

Philip: I would love to hear his story, what it was like from his point of view.

Rose: Marty never got in touch with Philip, he never called the number on the card. So we might not ever know what it was like from Marty’s point of view. Although, if you’re listening to this, Marty Rimm, and want to talk… email me. info@flashforwardpod.com.

The reason I told you this whole saga of Marty and Phlilip is to show that a country, like the United States, might indeed freak out about something happening online, and make policy decisions fueled by that freak out. And if we’re frenzied enough, we might make really rash decisions based on incomplete, or inaccurate information. And I don’t think it would be that hard to assemble incomplete information to make this argument.

So indulge me in a little bit more fantasy. Let’s say that something bad takes off online. Something like… what our fictional mother in the intro described. And a lot of what she said in her speech was based on real numbers. Between 2009 and 2017, depression among teens in the United States increased 69%. In the last decade, the youth suicide rate in the US increased 56%. According to PEW research, 59% of teens say they have been bullied or harassed online. A New York Times investigation in April found that white supremacists and mass shooters were connecting with one another online, and citing each other in their manifestos. Many of the mass shootings in the United States in the last few years have been carried out by men who were encouraged and radicalized on the internet. I’m not saying this to say that we should shut down the internet. I’m saying this to say that it wouldn’t be that hard for someone to connect these dots and argue that there is some kind of sickness spreading via the network.

Finn Brunton: Something deeply, cognitively, dangerous.

Rose: Today, a lot of parents parents of the United States feel helpless in the face of all of this information. I’ve talked to lots of parents who feel like somebody in charge should do something. Of course, that something will apparently never be sensible gun regulations. So we have to do something else. And maybe, that something else… is shutting down the source of all this information. Again, I’m not saying we should do this, I’m saying that this is an argument that I can actually see … kind of working.

And to push this kind of change through, in this fictional scenario I am building, we need to invent one more thing: a coalition of parents, mostly moms, who start to really lobby their politicians to do something. And there’s a very clear precedent that we can model this group off of — it’s called Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

You’ve probably heard of this organization, and its history is super interesting — we don’t have time to go deep but Patrons will get a Mothers Against Drunk Driving deep dive in the bonus podcast this week. But the short version is this: On May 3, 1980, a 13-year-old girl, named Cari Lightner, was killed by a drunk Driver in California. In September of that year, Cari’s mother, Candy, founded an organization to fight against drunk driving, called Mothers Against Drunk Driving. And MADD is interesting because it was very quickly very effective. In just a couple of years, they managed to change several state laws around alcohol consumption and driving rules, like changing the legal limit for blood alcohol to .08 instead of .10. In 1984, just four years after its founding, Mothers Against Drunk Driving had pushed through a federal law that forced states to raise the minimum drinking age to 21. There is so much interesting stuff to say about MADD, but for our purposes here we’ll leave it at this: grieving mothers — especially grieving middle class white mothers, like Candy Lightner, and like the mothers of these mass shooters, can be incredibly powerful lobbyists.

And this is the scenario that I’ve been thinking about for years, and that at this point I’m … sort of convinced could happen. A powerful mom-based lobby, perhaps called Mothers Against Digital Dangers, or Mothers Against Subversive Technology, yes I’ve designed them a logo. So this group decides that the root of all these mass shootings and the teen mental health crisis and fake news and terrible stuff is… the Internet. And they push to have it shut down. I actually think they’d find some support for this idea among politicians in the US. But ideally, they would have one more piece of the puzzle — an ever so slightly more authoritarian ruler. And when we come back, we’re going to look at some examples of Internet shutdowns outside the US, what they have in common, and how we might see similar tactics here. But first, a quick break, take your tinfoil hat off, breathe deeply, and remember, this is all made up… for now.

[AD1]

Rose: Okay, so here in the US, there has not ever been a state mandated Internet shut down. But around the world, they happen all the time. Last week, Iran shut down the Internet for seven days. Over the summer there were internet blackouts in Zimbabwe, India and Cameroon. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Internet has been on and off for a year and a half.

Chipo Dendere: So they’ll go for like three months straight with no Internet.

Rose: This is Dr. Chipo Dendere, a professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College who does research on internet shutdowns.

Chipo: We also have examples in Cameroon. So the southern part of Cameroon, I think the longest, the Guyanese lake; also three months, ninety days, without Internet, completely. In Benin. the government also just shut down the Internet. In Algeria last June — like a year ago — the government also shut down the Internet for a couple of weeks. We’ve also seen shutdowns in Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Rose: Not all of these situations are the same, but there are some commonalities. The big one is that the leaders of these nations have the authority to do something like turn off the Internet. Sometimes they give an explanation for why they’re doing it, and sometimes they don’t. Most of the time when they do give an explanation, it’s not totally truthful.

Chipo: Back in the day, when this first happened, there in Afghanistan, it was actually the Taliban that shut down the Internet. And they see that it was because the Internet was spreading anti-Muslim language, and that there was immoral material on the Internet, and they didn’t want people to have access to these things.

Rose: In Ethiopia, the government claimed that an internet shutdown was to prevent students from cheating on their exams.

Chipo: And so they say that we’re worried that students were sharing exam material via the Internet so that we just shut it down for the exam period. But then it went on for weeks and weeks.

Rose: In Cameroon, the government shut down the internet because they said it was being used to spread fake news.

Chipo: If you’re going through Cameroon — in southern Cameroon — you may be stopped at a roadblock, and you would have to show your phone. And you’d have to show your social media activity. And you have to open your WhatsApp. And because the government is really quite concerned that people are sharing all these falsehoods

Rose: Other times governments use the excuse of security. In the DRC they argued that the Internet was causing unrest which in turn was making the country unsafe.

Chipo: The Internet is leading to protests, and protests are leading to destruction of infrastructure. And we want to protect the infrastructure. So this is why we’re doing this.

Rose: But the real reason these countries shut down the internet is to maintain control. They don’t want their own people organizing and sharing information that might cast the government in a negative light. And sometimes they don’t want information about what’s happening inside the country to get out.

Chipo: The DRC case in January was really powerful, because people weren’t happy with the results of the elections. But the only message that was coming out of the DRC was the state controlled message that said, you know, people are fine. And we weren’t seeing pictures of protests, we weren’t seeing protesters online. So it was really easy for a lot of people to just be like: OK. There was an election. There was an outcome. Everybody’s happy.

Rose: It’s perhaps easy to say well, that’s happening over there, it couldn’t happen here. But it’s not just countries in Africa that play around with this idea.

Chipo: Most of them are in Africa, but we’ve also had incidences in India where they’ve shut down the Internet. In Iran, in Iraq, in Kazakhstan, in Morocco. So while sub-Saharan Africa tends to feature more, I think it’s kind of a global phenomenon.

Rose: In 2011, during protests in London, David Cameron, then the prime minister of the United Kingdom said that he was quote “working with the police, the intelligence services and industry to look at whether it would be right to stop people communicating via these websites and services.” Ultimately he didn’t do it, but he did consider it.

Looking at these shut down cases also gives us a chance to see what really happens when the internet gets turned off. And when we come back we’re going to dig into what might actually happen without the Internet, with one of my very favorite authors.

Tim Maughan: And I just remember having a sudden realization that this infrastructure that we very much depended on wasn’t necessarily permanent.

Rose: But first, a quick break.

[ADS2]

Rose: Okay so let’s say… that this coalition of moms that I’ve been talking about convinces a future authoritarian president of the US to shut down the public facing internet. What happens next? To answer that, we have to talk about what The Internet actually is.

Tim: To me, it’s anything that’s touched by IP, by Internet protocol. And this huge network that’s getting your food, and your drugs, and your crappy plastic goods, and everything it makes in your life capable from one side of the world to the other side, and also in theory taking the trash and the waste of that back, is still is very much tied into the Internet.

Rose: This is Tim Maughan, a journalist and author of the novel Infinite Detail, which is very good. And you don’t even have to take my word for it, The Guardian just named it the best sci-fi novel of the year! And Infinite Detail is about a world where people rebel from the Internet.

Tim: Was the book about? I say it’s about destroying the Internet and why we might want to.

Rose: The book follows different groups and characters with different perspectives on the Internet. You have your more intellectual activists, who are trying to push back against the corporate, top down, control of the Internet that we see today.

Tim: they are looking at it in a more experimental and more, kind of, artistic sense.

Rose: And these characters actually build a special, Internet free zone in Bristol, in England. . So if you go there, you can’t connect to your usual Internet networks; the wifi doesn’t work, your cellphone network isn’t going to connect you to Facebook or your email, but…

Tim: You can log on this other network, which is a very different type of network, not better built on Internet protocol. It’s built on mesh networking. And their argument really is that we have ceded too much control to the Internet for every aspect of our life, from the economy to surveillance, to how we consume, to our culture, everything has become far too centralized because the Internet.

Rose: And you see this argument a lot, right — when everybody is using the same algorithms to do things like find new music, or consume the news, it collapses down all the weird corners and communities online into one sort of homogenous soup. So, in the book, these characters want to break that monoculture, and encourage these small mesh networks that resists corporate control. But there’s another set of actors at work in the book, too, called Drone Gods.

Tim: Their concern — and this is one of my concerns, really, and I found they were the best way to articulate this — is not just that we’ve lost control our day to day lives on the Internet over how we use Amazon, or social networks, or whatever. We’ve lost control over politics, too, as a result.

Rose: And the thing that I think is so smart about Tim’s book, is that you kind of relate to both of these groups. It does kind of feel right now that something is wrong. Something is off balance. All these companies are enabling behavior that is bad for the world — whether that’s election tampering, or misinformation campaigns, or treating workers terribly, or pushing out small local businesses. It just feels like something is amiss in this world, even if you can’t quite put your finger on it. So while the more artsy activists in the book try to build an example of what the internet could be, Drone Gods have another idea.

Tim: Just break it all and start again, and see what happens. They’ve got that kind of anarchist, anonymous, kind of attitude towards it, that kind of chaotic attitude towards it. But the average I’m trying to make with the book is that neither of these groups have really planned for what happens next.

Rose: So, what does happen next? I’m not going to spoil the book here, you should absolutely read it, but let’s talk about what our world without The Internet would look like. So, without the Internet, you can’t do anything that relies on this internet protocol. Most importantly, that means you would lose access to this podcast! No, obviously that’s not the most important thing. The first thing you’d probably notice, is that you can’t really communicate with anybody. Chipo has experienced that first hand, trying to reach friends in the DRC.

Chipo: They told me that anytime I can’t reach them that means that the Internet has just been turned off.

Rose: And she says that the other thing you see — especially in Africa when there are internet shut downs — is that it’s almost impossible to pay for things.

Chipo: So, in most African countries, people use mobile money, something that we haven’t really got up to in the U.S., but it’s really popular everywhere else in the world. So, when the Internet shuts down, really there’s no banking that’s happening. There’s no transacting at all.

Rose: The thing that’s really scary about an internet shutdown isn’t that you woldn’t be able to use Twitter, or Facebook, or texting, or even that you wouldn’t be able to pay for some snacks in the airport. It’s that the internet, and internet protocol, touches almost everything these days.

Tim: An outage of this scale, the first place you might notice it is that, you know, things are playing up your Internet, playing up your emails. Not working. You can’t go on Twitter, you can’t go things. But very quickly after that, you might realize that there isn’t any food in the stores, right?.

Rose: If you think about a true, global, internet blackout, things get extremely wild pretty quickly. Now, in the scenario that we’re posting here in this episode, it’s not a global blackout. That would be super hard to do. The Internet is a pretty distributed global network, and shutting the whole thing down, all at once, would be pretty challenging. But even if the US decided to just limit the public’s access to the Internet — while still letting things like shipping and power and satellites and all those private uses go through, there would still be some real consequences. We know, for example, from modern internet shutdowns, that they are incredibly costly.

Chipo: So, we have data from Cameroon that say that when they shut down the Internet for about three months, they lost at least 2 billion in revenue.

Rose: If the US decided really and truly to shut the whole thing down, they would stand to lose billions of dollars. We can even get a little bit more precise with our estimate. The accounting firm Deloitte estimates that for countries with a high level of internet penetration, so the US counts under that umbrella, an internet shutdown costs $23.6 million per 10 million people who live in that country. The US’s population is currently 327 million people. So a temporary shutdown of the internet here would cost the country a cool $771 million dollars.

And that’s just a temporary shut down. If the US decided to abandon the public facing internet completely, tons of tech companies would just leave, and go places with less restrictive rules. A lot of them would probably go to China, where, as we talked about last week, there are over a billion potential consumers who would still have access to the Internet, as long as you play by China’s rules.

Chipo: Even in China, where they are very restrictive on how people can use the Internet, they also understand that the economic powerhouse depends on people being able to order things from Alibaba online, and all of these Chinese providers online.

Rose: Beyond the economic cost, there’s also the social one. Yes, the Internet can and is used to share horrible stuff. But it’s also often a lifeline for many people — particularly marginalized groups. The young queer kid in a tiny town full of homophobes, or the disabled person who can connect to their community from anywhere.

And yet, despite all the reasons that you should definitely not shut down the internet, Chipo notes that even if it might be obvious that shutting down the internet would be a terrible idea, that doesn’t mean it won’t happen.

Chipo: The thing is authoritarian governments, they don’t care. And this is something that it took me a really long time to just be able to say, look, there’s no fancy theoretical term that we should be using. The reality is very simple; is that people don’t care, because their goal is to hold onto power by any means necessary. So, if it means the country loses billions of dollars, and the poor become poorer, then that’s exactly what they’re going to do.

Rose: And this is why I still kind of think that there’s like a 2 percent chance of this weird, paranoid, future scenario I described playing out. Because I think many of us do feel some uneasiness about our modern digital lives. The way all of this stuff is controlled by companies who don’t seem to care about their impact on the world. The potential risks that our kids might face when they log on, the content they might see, the bullying they might face.

Tim: The scale of it, when you think about it too long, is absolutely terrifying. We live in a completely different world now than we did just when we were children. as far as the media, and news, and this surveillance technology works. It’s completely revolutionized everything, and it’s terrifying.

Rose: It’s totally normal, and honestly even, I think, even rational and prudent to be a little bit afraid of the Internet right now. And when we’re afraid, we make bad decisions. Remember Adam Green, from the 1919 episode, the historian from the University of Chicago; he had a warning for us that’s relevant here too.

Adam Green: I think Americans like to believe in their better angels. And I don’t care whether it’s in terms of dealing with digital platforms, dealing with social networks, dealing with political partisanship, dealing with implicit bias. We always have to remember that we are shaped by our worst demons as much as we are by our better angels. And if we are not in touch with the ways in which how easily those demons can be awakened; by misinformation, by prejudice. If we don’t find ways to protect ourselves from having those demons awakened, then we’re gonna be driven to action by those demons as much as we are going to be driven to action by our better angels. And that’s the kind of thing that can destroy our society. And so, I think, in terms of the future, we always have to remember that we have the capacity, really equal capacity, because of who we are as human beings, for destroying our society as we believe we have for advancing our society by our various discoveries, our various technologies, our various powers.

Rose: Or, in the words of Finn Brunton again,

Finn: We, as humans, are far more filled with latent psychopathology then we necessarily realize.

Rose: The Internet is incredibly powerful, and in many ways, that’s why we should fight for a better version of it. Even, Tim, for all his doom and gloom about today’s corporate controlled Internet, has the web to thank for something pretty important.

Tim: I was living in the U.K,. that’s come out the relationship. I didn’t want to get in a relationship. And then I met someone online, and actually someone I’d known for a long time online. And we started talking, and it turned into like a full blown relationship. And for the first few months of that relationship, it was a long distance relationship.

Rose: Spoiler alert: they’re married now. And without the Internet, that might never have happened. And this is maybe one of the reasons Tim thinks so much about the future of the Internet, and what we want it to be like.

Tim: It became very obvious to me how fragile that relationship could be because it was built on this infrastructure.

Rose: When the Internet was first invented, it was hailed as this revolutionary, democratic technology, where anybody could post and surf and build friendships, and create weird websites and make cool art. Today, thanks to our corporate overlords, we’ve lost that spirit in many ways, but I really do believe that we can get back to it. And in some ways, I think that this conversation about the Internet, and what we want it to be, and how to harness this technology for good over evil, has become a proxy for talking about the future more broadly. Do we want a world where fear and chaos win, where we build walls and sever connections between people, where we hand over all control to a handful of select bazillion dollar companies or humans? Or, do we want a humane, human centered future where we can have that connectivity and creative synergy and common collective action. I think that if we want to solve the world’s biggest problems, we have to have that latter thing. And we can get to this version of the internet, and thereby the future. It doesn’t even require a time machine! it just requires attention and effort and asking a lot of questions about what kind of tomorrow we actually want.

[music up]

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth. The intro music is by Asura and the outtro music is by Hussalonia. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Huge, huge thanks to Tamara Krinsky who played Billy’s mom on this episode, and also (did you notice?) played a time traveler dipping in and out of all the futures this season.

This is the last episode of the season. As Patrons know, I’ve been thinking a lot about what 2020 will hold for Flash Forward. I got really mixed feedback on these mini-seasons, some people loved them, some people hated them, some people loved certain mini-seasons and hated others. Patrons are going to get a whole big recap of what I have learned this season, and a sneak peak at what next season will be like, but let’s just say I’ll make some changes, based on everybody’s feedback. Also, as is the tradition every year, I’ll do a blog post recapping all the stuff that happened this year on the show, including guest demographics, all the books I read this year for the show, what I thought worked, what didn’t, and what I’m imagining for next year. Check that out in the next couple days at Flashforwardpod.com. Patrons will also get updates, even during the break, about how the show is going, and other fun secret stuff.

Speaking of patrons: this show right here, that you’re listening to, Flash Forward, is mainly supported by Patrons! If you like this show, and you want it to continue on to next year, the very best way to make that happen is by becoming a Patron. Even a dollar an episode really helps. You can find out more about that at flashforwardpod.com/support. You can also just donate one time, if you want, and you can also donate as a gift for somebody this holiday season! If you’re not in a place to donate, that’s totally cool. Another other great way to support the show is by heading to Apple Podcasts and leaving the show a nice review. I do read them all! Which means that I see people like ksemro who says “So glad this show was featured on 99% invisible or I wouldn’t have found it. I love the mix of fictional futures and scientific information. It’s been reminding me how much I used to love sci fi as a kid. Thank you for all your hard work on these wonderful episodes!” Thank you, friend! And thanks to Roman and 99PI for having me on recently, and hello to all of you who might have heard about the show because of that episode about peppers. I recently found some very moldy peppers I had brought back from that reporting trip in the back of my fridge. Your ears are a much better reminder of that story than the moldy peppers that I threw away!

If you want to suggest a future I should take on, send me a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. I love hearing your ideas! If you want to discuss this episode, or just the future in general, with other listeners, you can join the Flash Forward FB group! Just search Facebook for Flash Forward Podcast and ask to join. And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

Okay, and since it’s the last episode of the season, I’m going to reveal some of the references from this past year! A lot of people email me being like “what the heck should I even be looking for!?” so… here goes. Some of them are names of characters in the intro script, so for example, in the Polar Flip episode earlier this year, the two inventors in the intro sketch were named Roberta Peary and Ramona Byrd, after the North Pole explorers Robert Peary and Richard Byrd. In the CSI++ episode, all the characters were named after people from the My Teacher is an Alien book series by Bruce Coville, which was one of my favorites as a kid. Other times it’s the little clips that I play in the episode — so in the Ghost Bot episode I threw in a clip from The Good Place. In the Enter Night episode I played a clip from Are You Afraid of the Dark. So now you know what to look for! Go forth and find!

Okay, that’s all for this future and for this season, and this year! Come back next year, and we’ll travel to a whole bunch of new ones.

13 comments

[…] got a collaboration with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a story that takes place in the same world of the latest episode of her inimitable Flash Forward podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a show all about […]

[…] got a collaboration with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a story that takes place in the same world of the latest episode of her inimitable Flash Forward podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a show all about […]

[…] with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a narrative that takes place in the identical world of the most recent episode of her inimitable Flash Ahead podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a present all about […]

[…] with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a narrative that takes place in the identical world of the latest episode of her inimitable Flash Forward podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a present all about […]

[…] got a collaboration with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a story that takes place in the same world of the latest episode of her inimitable Flash Forward podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a show all about […]

[…] with Rose Eveleth, who brings us a narrative that takes place in the identical world of the most recent episode of her inimitable Flash Ahead podcast—which, to the uninitiated, is a present all about […]

[…] POWER: Mothers Against Digital Danger […]

[…] for the Producers Guild of America Awards, playing multiple characters on the futurist podcast FLASH FORWARD and continued work with Antaeus Theatre Company, where she is an Ensemble […]

[…] Eveleth’s short story Mothers Against Digital Danger doesn’t send all of civilisation back to its beginnings, just the […]

[…] Eveleth’s short story Mothers Against Digital Danger doesn’t send all of civilisation back to its beginnings, just the […]

[…] Eveleth’s short story Mothers Against Digital Danger doesn’t send all of civilisation back to its beginnings, just the […]

[…] Eveleth’s short story Mothers Against Digital Danger doesn’t send all of civilisation back to its beginnings, just the […]

[…] Eveleth’s short story Mothers Against Digital Danger doesn’t send all of civilisation back to its beginnings, just the […]