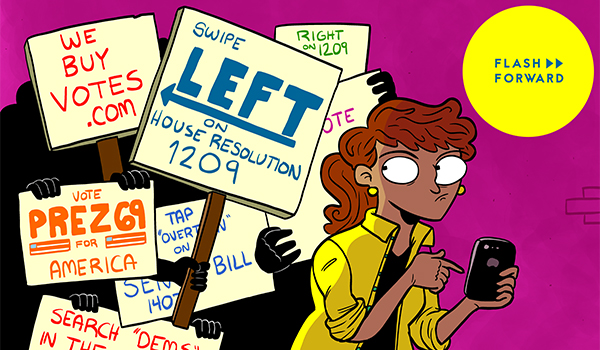

Today we travel to a future where America has converted to a direct democracy. Everybody votes on everything!

Hey, did you know it was an election year in the United States? I know, you’ve probably not really heard about this, it’s not like it’s on the news 24/7. But for all the coverage and the fights you might be getting into on Facebook, tons of people in the United States aren’t going to vote in this election. The Pew Research Center has some pretty depressing statistics on just how many Americans go to the polls every year.

People in the U.S. don’t vote for a lot of reasons. The main one is time. But the second most common answer (16 percent) that Americans give, when asked by the Census Bureau why they don’t vote, is that they weren’t interested. And eight percent of people said they didn’t vote because they didn’t like the candidates or the issues.

It’s no secret that Americans hate their government. In 2015, a Gallup poll estimated that only eight percent of Americans have faith in Congress as an institution. Eight percent!

So what if we did things differently? What if we put the vote back to the people, and had Americans actually vote on the issues directly. What if America was a direct democracy?

To find out what might happen we talked to Kerri Milita, an assistant professor at Illinois State University who studies direct democracy in America.

We also talked to talked to Daniel Castro who’s the vice president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation about what an accessible voting app would look like. A few years ago, they looked at accessible voting technology, and found that when you can let people vote on their own apps in their own places that are already safe and customized to them makes a big difference.

So let’s say that this all works perfectly. Just go with me to the utopia for a second. Everything works really great, everybody is happy, we’re all securely and safely writing bills and voting on our phones. And because there are no barriers to voting anymore, turnout and participation skyrockets. Now, most people vote! Yay! What does that United States look like when all the people who don’t vote today, start voting.

To find out, we called Sean McElwee, a policy analyst for an organization called Demos. Sean told us about his research on the differing opinions between voters and non-voters, which you can read here.

We also talk about security and voting, and what happens if nobody actually votes because they’re overwhelmed.

We didn’t get to talk about a few things in the show. Like how Sweden uses direct democracy, why Estonia has online voting and we don’t, the history of direct democracy, or the proposals to change the forms of democracy we see in the United States.

What do you think? Do you vote yes or no on direct democracy? Tell us! Send us a voice memo to info@flashforwardpod.com or call and leave a voicemail at (347) 927-1425.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth, and is part of the Boing Boing podcast family. The intro music is by Asura, the break music is by MC Cullah and the outtro music is by Broke for Free. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky. Special thanks this week to Dara Lind, who suggested this episode, and Rob Tannen, who provided valuable insight into election app design.

If you want to suggest a future we should take on, send us a note on Twitter, Facebook or by email at info@flashforwardpod.com. We love hearing your ideas! And if you think you’ve spotted one of the little references I’ve hidden in the episode, email us there too. If you’re right, I’ll send you something cool.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! We have a Patreon page, where you can donate to the show. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next week and we’ll travel to a new one.

▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹▹

TRANSCRIPT

Hello and welcome to Flash Forward! I’m Rose, and I’m your host. Flash Forward is a show about the future! Every episode we take on a specific possible or not so possible future scenario. Everything from the end of antibiotics, to space pirates, to a world full of face blind people. We start each future with a little trip to tomorrow, before jumping back to today, to talk to experts about how that future might really go down. Got it? Great.

Today we’re going to start in the year 2112.

Good morning Alexander. You slept for 6 hours and 24 minutes last night, with only one major interruption. Your new water regimen seems to be working. Would you like to review today’s votes?

Today there are 13 measure to vote on. You also have 28 measures you have not yet voted on. Would you like to see the measures that are expiring soon?

H. R. 3546 — Big Cat Public Safety Act — And act to amend the Lacey Act Amendments of 1981 to clarify provisions enacted by the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, to further the conservation of certain wildlife species, and for other purposes. Would you like to hear more about this bill and vote on it?

S. 2280 — Pro bono Work to Empower and Represent Act of 2015 or POWER Act — A act to promote pro bono legal services as a critical way in which to empower survivors of domestic violence. Would you like to hear more about this bill and vote on it?

S. RES. 230 — A resolution Designating September 25, 2015, as National Lobster Day. Would you like to hear more about this resolution and vote on it?

H. R. 394 — A bill to prevent the escapement of genetically altered salmon in the United States, and for other purposes. Would you like to hear more about this bill and vote on it?

GovTrac estimates that bill H. R. 394 has a 19% chance of being enacted.

Would you like to see how people in your area have voted on H. R. 394?

So far, no one in your area has voted on H. R. 394.

Would you like to see who has endorsed H. R. 394?

So far, no one has endorsed H. R. 394.

Would you like to hear the remainder of the measures you have not yet voted on?

Voting is important, Alexander. Your voice counts.

Rose: So this week’s we’re traveling to a future where the United States is a direct democracy. Everybody votes on everything, nobody elects representatives to go to Washington and do things for them. We’re going to focus on the US specifically, so, sorry friends in other countries, I haven’t forgotten about you, it’s just a little too much to try to think about how this would work in every country.

Now, in case you haven’t noticed, it’s an election year in the United States. But for all the lively Facebook debates you might be seeing in your feed right now, a huge percent of Americans will not vote in this election. And even fewer of them will vote in the midterm elections that follow. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2012, just 53.6 percent of eligible voters in the United States actually voted. And only 36 percent voted in the 2014 midterm elections. For comparison, in Belgium, 87 percent of the population votes. In Turkey, 86 percent do. In a list of 34 highly developed countries, democratic countries, the United States ranks 31st in voter turnout.

So, why don’t American’s vote? There are lots of reasons. Election day isn’t a national holiday, and for those with multiple jobs and families to take care of, finding time to stand in line and vote simply doesn’t happen. According to the Census Bureau, 28 percent of Americans who don’t vote said they skip the polling place because they are too busy. But the second most common reason, at 16 percent, is that they were “not interested.” And eight percent said they didn’t vote because they “disliked candidates/issues.”

You’ve probably heard this kind of thing before. Maybe you’re one of those people. Why vote? It hardly seems to matter these days. Right now, a lot of Bernie supporters I know are declaring that if he doesn’t get the nomination, they won’t vote in the general election at all. Younger voters, the people who fall into the, and I hate that I’m even saying this word on my podcast, but the “millennial” category, in particular are unlikely to vote. In 2010, 75 percent of millennials did not vote.

But, here’s a thing I think is important, and it’s not just because I am trying to defend the honor of my generation who seem to be at fault for pretty much everything going wrong in this country right now. It’s not that millennials aren’t political, or that they don’t care about politics. In fact, millennials are just as likely as past generations to do things like contact local government officials, and volunteer in their communities and go to protests or political gatherings. So they care about politics, but they don’t care about voting.

But it’s not just young people who are frustrated with the political system in the United States. According to a 2015 Gallup poll only EIGHT PERCENT of Americans have confidence in Congress as an institution. EIGHT PERCENT. That is … incredible to me.

So what if we did things differently? What if we put the vote back to the people, and had Americans actually vote on the issues directly. What if America was a direct democracy?

Kerri Milita: So direct democracy in America means something very specific, it means that the public not just voted on their phone for a bill but the public actually went out and wrote the bill basically, authored a policy proposal, you go out you collect some signatures and once you get enough signatures then you stick it on the ballot and then people vote it up and down on election day. And that’s called initiative and referendum and that’s what direct democracy really means in the United States.

Rose: That’s Kerri Milita, she’s an associate professor of political science at Illinois State University and she studies direct democracy.

Rose: Now, there are actually states in the America that have direct democracy systems.

Kerri: 24 out of the 50 states have what California has, where you basically can write your own proposal, amend your state law or you can amend your state’s constitution so it’s about half the states have it.

Rose: And in some states, this goes really well.

Kerri: Initiative states have public approval levels that are 15-30 percentage points higher than non initiative states, so it’s a sizeable bump. States that have direct democracy, the electorates trust their governments more, it’s like a safety valve where they know that if the legislature oversteps its bounds they can correct it, they like government more they feel more efficacious, they’re more likely to believe that ‘hey we can do something to change it if we’re unhappy about it, they’re more likely to turn out to vote, they’re more likely to possess high levels of political knowledge. So even today there is sort of this quasi utopian tendency in the direct democracy states.

Rose: And in other states it does not.

Kerri: But on the other hand I would say look to CA for the dystopian future. It’s not uncommon at all to have 10-15 ballot measures on a ballot every year. And that’s unusual for American direct democracy. We call it a high use state, where they vote on so many that there’s high levels of abstention, so what you end up with is a very small level of elite voters that determine the policy, which isn’t that much more fair or utopian than having legislators who take big donations from corporations deciding the policies. So wind up back with that, you know the special interest buying out votes essentially.

Rose: I used to live in California, and it seems like the state can show us a couple of ways in which direct democracy can, go wrong. The first is just the number of ballot measures. I remember going to the polling place, and being met with some proposals that I had never heard of, and really had no idea how to vote on.

And Kerri says that when that happens people have two main reactions.

Kerri: Yeah so there’s two strategies and we haven’t quite pinpointed down what types of people do what, but the first strategy is that if you see something that’s really confusing you vote no, we call it the confusion penalty, we automatically reject it if you can’t understand it. And the second group of people do what we call the rage quit where they don’t vote at all. So a really confusing ballot measure actually has a low chance of passing on election day, which, I don’t know, maybe that’s good.

Rose: We’re going to come back to the scale of this idea in a bit. But it’s not just that are were SO many ballot measures that go through the California referendum system. It’s also that some of them sort of represent what the founding fathers were worried about when they created America’s representative democracy.

The founding fathers worried about the “tyranny of the majority” — the idea that if put to a popular vote, the majority might vote to truly harm a minority group. And we saw that in California not that long ago. In 2008, there was a ballot proposition in California that would make same-sex marriage illegal. It was called Proposition 8, or Prop 8. And, on the same day that President Obama was elected, Californians voted to pass Prop 8, and ban same sex marriage. Now if this isn’t a good example of the tyranny of the majority voting to take fundamental rights away from the minority, I’m not sure what is. Today, Prop 8 is no longer valid, since the US Supreme Court ruled that bans on same sex marriage were unconstitutional. But if we were run by a direct democracy system, we might still be living in a world where gay people can’t get married.

But Kerri says that there are ways to make a direct democracy system better than the one California has. And, weirdly enough, she says that actually the best thing to do is to make it harder to get something on the ballot.

Kerri: Yeah my home state, I come from Florida, I teach in Illinois but I’m from Florida. Florida has, the legislature has restricted the initiative process, they have this requirement that and initiative has to pass by a supermajority so it has to have 60 percent of the vote, it’s actually fairly costly to get a measure on the ballot, it’s actually fairly costly to get a ballot measure, you have to have just under a million signatures, which even for Florida is quite a lot, and they have to be distributed evenly. So states that make it a little tougher to qualify for the ballot I think experience more of that utopian side than dystopian. I think direct democracy works less when it’s difficult to use and we use it sparingly, because then it’s a rare event, it’s kind a treat, because then it makes it efficacious they get informed, they trust government more, but if you make it a routine day to day thing it would lose a lot of its sparkle.

Rose: Now, this seemed, to me, like the opposite of what would happen. If you make it really hard to get a ballot measure on, won’t it just be the groups with tons of money who can put a ballot measure through? Doesn’t that just mean that the really rich people are in control again?

Kerri: That was my thought too, and that was basically what I wrote my dissertation on, was this issue of who’s funding the ballot measures in states here it’s really tough to put one on the ballot, because I wrote this in Florida where it really is difficult to put a proposal on the ballot. And what I found was the opposite, it was that states that make it harder to put a ballot measure on the ballot, well first of all they have fewer measures on the ballot, no surprise there, but what I didn’t expect to find was that when you make it tougher to put initiatives on the ballot the initiatives that qualify tend to be ones that were initiated by citizen driven groups, sort of volunteer citizen groups, no the deep pocketed special interests. Which to me was incredibly counterintuitive.

Rose: And the reason, she says, is pretty simple.

Kerri: And the reason why is that when you make it more costly to use direct democracy interest groups don’t want to invest their resources in that effort unless they think that their measure can pass. And we know that confusing ballot measures, like really technical ones that have to do with industrial regulation, are tough to understand and are more likely to suffer that confusion penalty from people who get angry at it and vote no, or just abstain entirely. So we actually find the opposite, the tougher you make it to put an initiative on the ballot you get more of those easy to understand measure that people can make informed decisions on.

Rose: So, we have some precedent for direct democracy in the United States, but it’s on a state by state basis, and it’s not on EVERY single piece of the government, just one or two bills a year. When we come back, we’re going to talk about what might happen if we tried to apply this concept to the entire country, how those votes would be collected, and what could go so, so very wrong. But first, a quick break.

[[AD]]

Okay so, this week we’re traveling to a future where instead of electing politicians, Americans take matters into their own hands, and have to craft and vote on every bill themselves. We’ve talked about how certain states have a certain kind of direct democracy, but let’s look at how this might work if applied to the entire nation.

So let’s talk about scale. There are a lot of bills being discussed in Congress right now.

Kerri: Yeah they get around to it between fundraisers.

Rose: From 2013 to 2014, the House of Representative considered 3,809 bills and they passed 223. The Senate looked at 1,894 bills and passed 356 of them. And that’s just national politics. If you had to read and vote on every one of those considered bills, that’s 15 things to look at and vote on every day. Here’s another way to think about it: 2013, the Federal Register, which is this daily newspaper type thing that records what’s going on in Washington was 80,462 pages long. I like to read, and I don’t think I read 80,000 pages every year.

And that is just too much for us to all handle. I mean, in California, where you get 10-15 bills every YEAR, people still abstain at really high rates.

Kerri: We the people get very fatigued very quickly and very easily, I mean you give us 15 a year we get kind of tired and start slacking off a bit. we do pretty good with 1-4 but you give us any more than that we stop paying attention or abstain from voting.

Rose: Which brings us to another piece of this possible future. If we’re going to have people drafting and voting on bills all the time, it doesn’t make sense to force them to go to a polling place every day. So this future comes with some new technology too: a voting app.

Now voting via a website or an app is something that people have been talking about for a while, but it’s really hard to actually do. But one of the advantages of being able to vote using a device, and preferably to be able to vote using your own device, in your own home, is that it makes voting way more accessible.

Daniel Castro: Yeah absolutely so one of the biggest you know positive changes that we can make in voting systems is to allow people to vote on the tools that they already use on a day to day basis so using their own you know, iPhone if that’s what they’re familiar with or their own home computer that they have set up for them at the right height for their own body. Those are the kinds of things that are very powerful for actually letting people interact.

That’s Daniel Castro, he’s the vice president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, which is a think tank focused on innovation. And a couple of years ago, his team took a look at voting technology. And what they found was that making voting easier, by letting people use devices that are already customized to their needs, is a huge deal.

Daniel: And it’s also in the environment that they’re at is not only the tool. You know one of the challenges that people have with going to a polling place today is that you know it can be noisy if you have PTSD you don’t want to be in a loud crowded environment you want to be at home. If you you know have social anxieties you know you don’t want to you know go and interact with somebody you want to be in the comfort of a familiar place like your home to do something that can be you know stressful which is voting and making decisions. So there is a there’s a lot you can do by you know allowing people to vote with tools their comfort with comfortable with an environment that they’re comfortable with.

Rose: They also found that giving people more time to vote can make the whole experience better for everybody.

Daniel: I mean one of the biggest changes in our research was that you know people want to be able to use something to assist them in making decisions so they want to be able to basically research who’s on the ballot as they are voting or at least do it before hand and kind of bring that information with them. And it’s often kind of difficult to do or not allowed or people aren’t sure if it’s allowed and so they just don’t do it. But you you know you go on these you go to these ballots and you you realize there’s something on there that you forgot to look up. You realize there’s a. You know a referendum on the ballot and you actually don’t know how you feel about it you’re not sure exactly what the wording means and you know you’re trying to make the decision you feel pressured to do it quickly because you know you’re in this kind of public place. Maybe there’s a line you know maybe there’s something you have to go to next and that’s a very different experience than you know being in an environment where there’s no time constraints. You know you can you can start and stop at your leisure. You can you know use additional reference material and that can change just kind of the you know basically if you’re an informed voter or not and how information shapes your decisions.

Rose: Now, if everybody is voting on their phones all the time, there are some weird things that would have to change about campaign rules and all of that.

Daniel: Right now a lot of the campaigning laws are based around polling places, you can’t campaign within 100 feet of a polling site. If you’re voting at home you know suddenly that changes you know the polling sites the individual home or the individual as they’re moving throughout the city with their mobile device. And so those campaign laws don’t really work anymore and so I think you know that will be something that will have to be addressed in the future because you know if you can vote when you’re sitting in front of a billboard that says you know vote for so-and-so or you know or scan here to vote for me or something and that just changes kind of the political campaign environment.

Rose: But those wouldn’t be so hard to figure out, I don’t think.

So let’s say that this all works perfectly. Just go with me to the utopia for a second. Everything works really great, everybody is happy, we’re all securely and safely writing bills and voting on our phones. And because there are no barriers to voting anymore, turnout and participation skyrockets. Now, most people vote! Yay! What does that United States look like when suddenly the almost half of the population who doesn’t vote today, now votes?

Well, America probably looks really different. Because voting and not-voting in this country is really clearly tied up in two things.

Sean McElwee: The United States has the most stratified of rich countries of turnout based on income and education.

Rose: That’s Sean McElwee, he’s a policy analyst at an organization called Demos, which studies democracy in America. And his research focuses on the differences between people who do vote, and people who don’t. And those groups, it turns out, have really different opinions about things.

Sean: The sort of going opinion in political science for a good amount of time was that the non voters and the voters were, voters were essentially a representative slice of the American population essentially like a good weighted sample or whatever but what the more recent research has shown that that’s not true. And on core issues related to the size of government and class and redistribution we actually do find differences and that’s because as I argue in my piece that one of the key divides in voting is race and is class and those are also places where you have really different opinions about the shape of government in American life.

Rose: So in Sean’s research, he found that on certain topics there were HUGE separations in what people who did vote wanted and what people who didn’t vote wanted. So, 46 percent of non-registered voters supported the idea of free community college. Only seven percent of registered voters agreed. Just over 20 percent of non-registered voters agreed with the statement “government aid to the poor is good.” And among registered voters, more people actually disagreed with that statement than agreed with it.

And when you look more closely at these groups, and separate them by income levels, you find even bigger gaps. Sean compared voters who earn over $150,000 a year with non-voters who earn less than $30,000 a year, to see if their answers were different. And they really really were. Poor non-voters wanted the government to increase services, increase spending on the poor, guarantee jobs and standards of living and reduce inequality. Rich voters answered completely the opposite, they opposed, on the whole, every single one of those things.

So, if everybody voted, what you would see is a pretty radically different allocation of government resources.

Sean: Internationally there is a very strong correlation between voter turnout and size of government. There’s also a very strong correlation between sort of low income low education turnout and services for low income low education people. So I think that if you had higher levels of turnout you would have certainly more responsive and representative government.

Rose: But there’s also a dystopian future to be had here, if that’s more your style. Because there are a couple of things that could go very wrong in this system. We’ve already talked about being overwhelmed by the amount of stuff we’d have to vote on.

Rose to Kerri: My favorite ones that I found was a resolution naming September 25, 2015 as National Lobster Day. So you can vote on that if you want.

Kerri: See, and I hadn’t thought of that. I want to say it doesn’t matter, but maybe there are big spillover effects and I would automatically say oh this doesn’t matter.

Rose: But there’s another huge problem here that has to do with online voting. Which is that it’s really, really hard to make an online voting system that is secure. And when it comes to determining the future of our government, you really want that system to be secure.

In 2010, Washington D.C. was working on an internet voting system that would let absentee voters and voters abroad go online to cast their ballot. Before they actually launched the system, they opened it up to security researchers to see if they could break it. After just 36 hours, a team of researchers at the University of MIchigan in Ann Arbor had pretty much completely infiltrated the system. And the people overseeing the website didn’t actually notice the hack for two days. So, D.C. doesn’t have an online voting system.

There is online voting elsewhere. Estonia has had online voting since 2005, and today about a third of their citizens vote online. But the Estonians have a few things that make that a little more plausible than it is here. And that same Ann Arbor team who hacked the D.C. system actually says that the Estonian system is vulnerable to attack too.

So in the dystopian version of this future, everybody is totally overwhelmed with the number of things they’re supposed to have opinions about. People that actually do vote are probably going to make some bad decisions simply because they’re uninformed about what they’re voting on, they’re stressed out and overwhelmed.

Kerri: If you pull back to the national level and we’re voting on Lobster day, we’re voting on trade policy, we’re voting on Hey do we build that wall? Then I think you’re going to get people who actually do vote are probably going to make some bad decisions.

Rose: And other people are going to stop voting altogether. And the online system could be hacked, with votes sold to the highest bidder. All you need is money to win an election.

Which, actually kind of sounds like what we have now?

Kerri: I actually don’t foresee that future as being particularly utopian or dystopian, I don’t see it as being all that different from what we have today.

Rose: That’s all for this future. Direct democracy is a huge topic, and I know we only talked about America here, but we’ll post links and more information on all of this in the show notes. Special shoutout to any Swedes who are listening — I know you all have a form of direct democracy nationally, and that’s super interesting. More on that, too, on our website.

What do you think? Do you vote yes or no on direct democracy? Tell us! Send us a voice memo to info@flashforwardpod.com or call and leave a voicemail at (347) 927-1425.

Flash Forward is produced by me, Rose Eveleth, and is part of the Boing Boing podcast family. The intro music is by Asura, the break music is by MC Cullah and the outtro music is by Broke for Free. The episode art is by Matt Lubchansky.

If you want to suggest a future, respond to this future, or just say hi, you can find us on all kinds of social media sites. We’re on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, Tumblr, Instagram, pretty much any place you want to be. You can also send us an old fashioned email, at info@flashforwardpod.com.

And if you want to support the show, there are a few ways you can do that too! We have a Patreon page, where you can donate to the show. But if that’s not in the cards for you, you can head to iTunes and leave us a nice review or just tell your friends about us. Those things really do help.

That’s all for this future, come back next time and we’ll travel to a new one.

15 comments

Someone might want to tell the person who was speaking about taking your time/ptsd/looking stuff up about Washington state.

All of our non-caucus voting is done by mail. In every county, for every election. You have plenty of time and all the privacy you want.

Yes! Daniel’s point I think was that in places where you can do that, people are happier and make more informed decisions than in places you can’t. In fact one of the teams on the project was from the University of Washington! http://www2.itif.org/2014-nist-webinar.pdf

I don’t think a “pure” direct democracy would ever work well. Josia Ober at Yale has an interesting idea on using weighted expertise to balance the “tyranny of the majority” with expert opinion as it related to an issue in a hybrid system. Other aspects of a “better” system would have to be implemented to fend off corruption.

[…] https://www.flashforwardpod.com/2016/04/19/episode-11-swipe-right-for-democracy/ […]

Voting by internet (including voting via an app) is a TERRIBLE idea. http://boingboing.net/2016/04/21/why-internet-voting-is-a-terri.html

Yep! We get into some of these points in the episode!

This was one of your best episodes yet, in this politics nerd’s opinion! Love it!

[…] Eveleth imagines this future on a recent episode of her podcast, “Flash Forward.” She talks with a few policy analysts and researchers […]

[…] So what if we did things differently? What if instead of voting to elect representatives to vote on issues on our behalf, everybody writes bills and votes on issues themselves directly. There is still a president who deals with nationwide issues, and foreign politics, but when it comes to bills that today would be considered by the House and Senate, those are now put to directly to voters. What would that United States be like? This is the future we travel to this week on my podcast, Flash Forward. […]

[…] maakt zich zorgen om het geringe aantal stemmers bij de verkiezingen en onderzoekt daarom het scenario dat je niet één keer in de vier jaar gaat stemmen, maar elke dag even via een app ove…. Swipe right for democracy, zoals ze het mooi noemen. Daar zitten uiteraard nog wat haken en ogen […]

[…] example, as noted by Flash Forward’s Rose Eveleth, there’s considerable evidence that the wealthier you […]

Just FYI, Sweden doesn’t have a direct democracy at all. Only one of the political parties tried electronic voting. The paper you linked to is a case for direct democracy in Sweden but not any actual existing system. Direct democracy only exists in Switzerland, and some US states as you mention, which is what that paper goes into.

Plus in Switzerland, voting is done by mail. So it is exactly this case of having the time to decide. However, because of the frequency, once every two months, people are easily overwhelmed and voter turn out is rather low.

You’re right! I mixed up Sweden and Switzerland in this episode. I sent out a correction email/note at the time but it’s hard to do corrections in podcast form!

Brigade’s solution: seamlessly connect all the relevant stakeholders by giving users the opportunity to find out who represents them and what they stand for, giving elected officials, campaigns and advocacy groups the opportunity to find new supporters.